Liber Linteus

Mummified Language

|

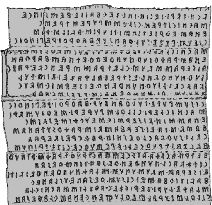

After this work was published, the wrappings were orthocromatically photographed (using light without a red spectrum) by Josef Eder, who was an Austrian specializing in the chemistry of photography. The results were much better than a previous attempt in 1870 by Croatian photographer Ivan Standl, with the text being captured well on film. Other experts of the time contributed to the study. Julius von Wiesner, a Professor of Botany at the University of Vienna, performed a chemical analysis of the wrappings and ink on them. The hairs of the mummy were examined by Austrian anatomist and histologist Victor von Ebner. This scrutiny spawned many books, with some having very serious scientific outlooks while others were more science fiction. Many scientists traveled to see the articles for themselves. One of these was Gustav Herbig, a German linguist and Estruscologist (one who studies Etruscian). While working with the wrappings to restore them in 1911, he found a new fragment of wrapping with writing on it amid the unwritten bandages. This piece was sent to Dr. Rudolph Robert at the Institute of Chemistry, Pharmacology and Physiology. There, it was discovered that the wrappings were saturated with balm resin and a harmful iron oxide, which would have to be removed. Little more progress was made with the wrappings until in 1932, when the first attempts were made on it to photograph it using the infrared spectrum, in an attempt to recover the parts that had become unreadable. This worked quite well, and in 1934, a series of photographs were made of 90 of the lines, making them much easier to read. The Liber Linteus was kept in a safe for storage during World War II. After that, they were returned to the Zagreb Archaeological Museum in Croatia. Today, the mummy is on exhibit, but the Liber Linteus itself is kept in a safe to help preserve it. Construction  The final resting place of the Liber Linteus: the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb The Liber Linteus is not simply a long scroll of continuous writing. When all of the known pieces are lined up, it resembles a book that has all its pages removed and set flat, one after the other. There are twelve of these pages, or columns, reading from right to left. Much of the first part is missing, but the text is almost complete near the end. The book ends with the last page being blank, but the ends of the wrappings are in tact, showing it is the actual end of the writing. In use, the Liber Linteus would have been folded back and forth along the column breaks, like an accordion, making each page be two of the columns, back to back. The columns are divided into a total of 230 lines and contain 1200 legible words. The ink of the writing is actually in two colours, with black being used for the letters and red being used for the diacritics and lines dividing the text. A red horizontal line is used to mark the beginning of a paragraph. When it was used to wrap the mummy, the Liber Litneus was torn into 5 strips, or binds, most being around 300cms in length. These binds ripped horizontally, across the entire length. Bound up as a book, it would have been roughly 40-44cm tall, 30cm wide, and 12cm thick. Not only was it Etruscan, but it was the longest ever preserved inscription in this language. While the age of the Liber Linteus is unknown, experts have compared the shape and styles of the characters in the text to other Etruscan artifacts. While the actual date is still debated, with possible times being somewhere between the 3rd and 1st centuries BC, the best estimate is probably around 250 BC. They further conclude it was produced when the Etruscan language was still largely in use, as it would have been produced by a priest or educated person. Contents  Reproduction of one of the columns Some words have been translated, so it is possible to guess at the meaning of the text. The most likely theory is that it is some kind of religious calendar. The names of gods have been discovered along with various dates. Similar texts have been found in Roman artifacts, giving details and dates of ceremonies and rituals. This idea is reinforced by the repetition of certain words and phrases, like would be used in a religious litany. Some of the names refer to local gods, so it is possible to narrow the probable origins of the book. Another clue is the form of the letters. It most likely came from an area southeast of Tuscany, near Lake Trasimeno. It was there that four major Etruscan cities were originally located, and they would have had a few temples that might have produced the book. The Mummy Some information was also discovered about the mummy. At first, all they could determine was that it was a female, and the odd nature of the excavation and sale did not give any extra clues. It was thought that she might have some relation to the Liber Linteus or the Etruscan people, but a papyrus scroll that had been buried with her identified her as an Egyptian. Her name was Nesi-hensu, wife of a Thebes tailor named Paher-hensu. How the wrappings were transfered to Egypt will probably always remain a mystery. They may have been taken to Egypt around 80 BC, when many Etruscans fled from the Roman consul Sulla during the Roman-Etruscan Wars. No other similar wrappings have every been discovered, and the large body of text is still mostly undeciphered. The Liber Linteus, with its unknown meaning and origins, will remain one of the world's oddest language artifacts. |

| Liber Linteus - Mummified Language | ||||||||||

| Writer: | Lucille Martin | |||||||||

| Images: | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Sources: | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

All images are Copyright - CC BY-SA (Creative Commons Share Alike) by their respective owners, except for Petey, which is Public Domain (PD) or unless otherwise noted.

comments powered by Disqus