Liber Linteus

Mummified Language

|

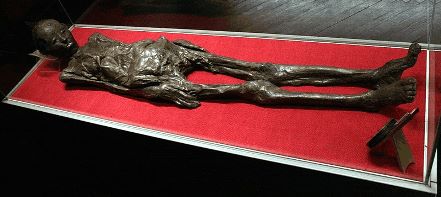

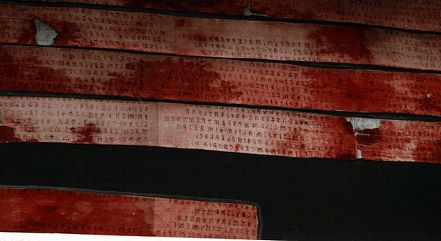

Ancient artifacts are usually made of something durable, like stone, clay or preserved wood, to help them survive the centuries. One, however, is made of cloth, and is actually a book. The Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis (Latin for Linen Book of Zagreb) is the only book made of linen in existence. It is largely untranslated because it is written in the Etruscan language, which itself is largely unknown, and is the longest text of Etruscan. What makes the Liber Linteus even more unique is the way it was preserved. It was discovered as bandages, wrapped around an Egyptian mummy. The original book had been torn into strips and used to bind the body. This is one of those times in which the items of a mummy are the more valuable finds. Etruscan The significance of the Liber Linteus being written in Etruscan is that so little remains of the language today. It was spoken and written in the Etruscan civilization that existed in what is modern day Italy in a time before the Roman Empire. It was the rise of the Romans and their language, Latin, that replaced the Etruscan people and language. Originally, Etruscan was widespread over much of the Mediterranean. This can be seen by the thousands of short inscriptions found on so much of the regions, dating back to 700 BC. Beyond Italy, Etruscan inscriptions have been found in the Balkans, Africa, Corsica, Elba, Gallia Narbonensis, Greece and the Black Sea. A few Romans were known to be able to read Etruscan, the last one being the Roman emperor Claudius. He was the author of an extensive twenty volume writing on them. Latin authors wrote about how rich the Etruscan literature was, however, the Liber Linteus is the only book that has survived the ages. Even if more text of it existed, Etruscan would still be difficult to analyze because it is a language isolate. No other language resembling it has been found in Europe or anywhere else. Even the Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus recognized this, describing it as a language that was unlike any other. Some aspects of Etruscan remain as part of Latin. A few dozen Etruscan words and names were borrowed by the Romans, and some of those survive today in modern languages. One significant contribution Etruscan had was the Latin alphabet. The Etruscan alphabet was adapted for Latin and used 26 letters. Purchase  The Zagreb mummy on display, without wrappings How the mummy and wrappings were first found goes back to 1848. Mihajlo Barić was a secretary in the Austro-Hungarian Royal Chancellery who resigned from his post and took off on a tour of several countries. While in Alexandria, Egypt, he found the opportunity to purchase a sarcophagus containing a small mummy as a souvenir. It is unclear who the sellers were, but they were likely to be grave robbers or antique traders in Alexandria. He had it shipped to his home in Vienna, where he put it on display in a glass cabinet in the corner of his sitting room. The mummy was presented upright, held in place by an iron rod. Barić's home had other oddities and art collections he had acquired, so it was right at home. During most of the time it was there, the mummy was still wrapped, except for its head, which Barić had revealed, perhaps for shock value. It is said that he would show it to guests in his house and claim it was the embalmed corpse of King Stephen of Hungary. He doesn't seem to have noticed the writing on the wrappings, at least not at first, since the writing was on the inside of the linen. Later, he had the wrappings completely removed and put on display in another glass case. It was in this way that both mummy and wrappings remained until Barić's death in 1859. It was then that his brother Ilija, a priest in Slavonia, became executor of Barić's will. Having no interest himself in the mummy, Ilija donated it and the wrappings to the then State Institute of Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalamtia in Zagreb, now the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb. Examinations Upon arriving at the Institute, the mummy and wrappings were put under the supervision of Sabljar, and he was the first to catalogue them. Sime Ljubic replaced him in 1871, becoming the curator of the Museum. Ljubic was the first professionally educated classical archaeologist of this institution and it was his idea to put the Egypt collection in order. Ljubic invited German Egyptologist Heinrich Brugsch to examine the remains. Brugsch was the first who noticed the text, but believed it to be Egyptian hieroglyphs, so he paid it little more attention. It is said that he would show it to guests in his house and claim it was the embalmed corpse of King Stephen of Hungary. The second expert to examine the writings was the English world traveler Richard Burton, who was also a friend and donator to the Institute. He and Brugsch discussed them in 1877 and realized that the writing was not Egyptian. They recognized the possible importance of the finding and believed that they were, perhaps, even a transliteration of the Egyptian Book of the Dead in Arabic. After realizing that was not the case, Burton had the idea that the script of the bandages was runic and published his ideas in the Royal Society of Literature of the United Kingdom in London in 1879. This was the first time the Liber Linteus was presented as an academic prospect to the rest of the scientists of the world.  The Liber Linteus on display The wrappings were sent to Vienna in 1891 to be examined more thoroughly by Coptic language expert Jacob Krall. He expected the writing to be Coptic (Egyptian written in Greek letters), Carian (an extinct language of the Anatolian branch of the Indo-European language family) , or Libyan (the version of Arabic used in Libya), but found them to be Etruscan. He was the first to realize this, and he reassembled the strips into the proper order, although he was not able to translate them completely. This work shows that the linen wrappings were part of a large manuscript. Not only was it Etruscan, but it was the longest ever preserved inscription in this language. Krall published his findings as Die etruskischen Mumienbinden des Agramer National Museums (The Etruscan mummy wrappings of the Agramer National Museum) in Denkschriften der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Proceedings of the Imperial Academy of Sciences) in 1892. It remains to this day a significant study of both the wrappings and the Etruscan language. |

| Liber Linteus - Mummified Language | ||||||||||

| Writer: | Lucille Martin | |||||||||

| Images: | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Sources: | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

All images are Copyright - CC BY-SA (Creative Commons Share Alike) by their respective owners, except for Petey, which is Public Domain (PD) or unless otherwise noted.

comments powered by Disqus