|

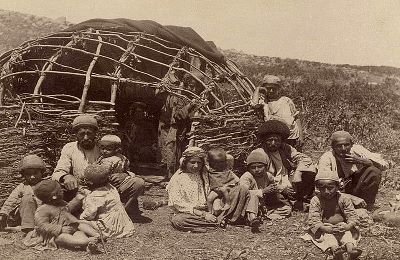

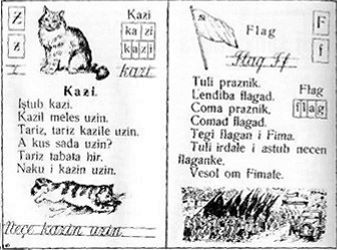

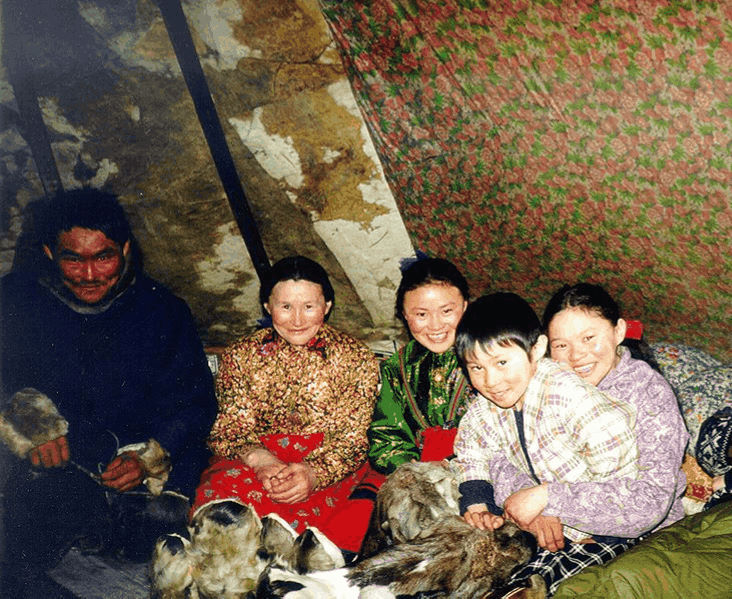

There are thousands of languages that are in danger of becoming extinct. Here, we will be looking at three of them that are a member of the Finno-Ugric family: Veps, Nenets and Komi. If you mention the Finno-Ugric language group to a language geek (since a non language geek will just look at you like you've grown a third head), chances are they will only be able to tell you of two or three languages in it: Finnish, Estonian and Hungarian. There are, however, as with most language groups, a number of lesser known related languages. We are going to look at three of them. Veps Whether it can be revived... or not will depend on how many of these children will pass it on to the next generation Veps, or Vepsian (native: vepsän kel’, vepsän keli, or vepsä) is spoken by, unsurprisingly, the Vepsians (also known as Veps). These people mainly live Russia now, and the language has three main dialects, spoken in specific regions. Central Veps is spoken in the Saint Petersburg region and western Vologoda Oblast. Southern Veps is also spoken in the Saint Petersburg region. Northern Veps, the most distinctive dialect, is spoken south of Petrozavodsk and north of the river Svir. Speakers of this dialect refer to themselves as "ludi" or "lüdilaižed".  A Soviet textbook for native speakers of Veps printed in the 1930s. Veps belongs to the Balto-Finnic branch of the Finno-Ugric languages and has close ties to both Karelian and Finnish. It only has approximately 6 thousand speakers, a sharp drop from a reported 12 thousand from Soviet statistics in 1989 (although all the Soviet statistics related to this are questionable), and that is largely in the older generation; younger people are not likely to learn it. Efforts were made to revive it and at the start of the 20th century, schools were started for teaching Veps. At the same time, a written version was created using a form of the Latin alphabet. Veps primers and text books were published starting in 1932, but an assimilation policy was introduced in the Soviet Union, and with the Vepsians being a minority group, these schools were closed down, the teachers were thrown in prison, and the textbooks were burned. Many Vepsians gave up the language and, being surrounded by Russians, adopted Russian as their language instead. In 1989, efforts were restarted to revive the language, but they have not been largely successful, and the number of native Veps speakers continues to decline today. Now, In Russia, over 350 children are learning the Vepsian language in five national schools. Whether it can be revived and the decline reversed or not will depend on how many of these children will pass it on to the next generation. Nenets Another Finno-Ugric language, belonging to the Samoyedic branch, is Nenets (native: Ненэця’ вада / Nenėcjaˀ vada). The name "Nenets" is taken from their word for "man". The native term for their language is "n'enytsia vada". And older term "Yuraks" is more widely known outside of the former Soviet Union and is taken from the Komi word "yaren" referring to Samoyeds. It has two main dialects, spoken in northern Russia by the Nenets people. The first dialect is Tundra Nenets and is more widely spoken with over 30 thousand speakers than the second dialect, Forest Nenets, which has just 1-2 thousand speakers. Unlike the dialects of Veps, which are mutually intelligible, Tundra and Forest Nenets have only a very limited mutual intelligibility, so much so that they are sometimes referred to as separate languages. Both have been greatly influenced by Russian, but Tundra Nenets has also been influenced by Northern Khanty and Komi, while Forest Nenets has adopted aspects of Eastern Khanty. The dialects of Khanty are mutually unintelligible, so these influences further divide the Nenets dialects. Komi will be discussed further later.  Nenets family in their chum The Nenets were first written using pictographic symbols called "tamga". Orthodox missionaries, like modern linguists, tried to create a written form for Tundra Nenets and in 1830, archimandrite Venyamin Smirnov published some religious texts using one of these forms. In 1895, some spelling books for Tundra Nenets were created, but they did not last. A literary language for it was established around 1931 using a Latin alphabet, but this was changed to Cyrillic in 1937 and is still in use today. Forest Nenets was only first written in the 1990s using the Cyrillic alphabet as well. Both of the Nenets are considered endangered languages, but Forest Nenets is on the seriously endangered list, which encompasses those languages with few children learning the language. Komi If a language could have an identity crisis, .. Komi would be a likely candidate for one. Now Komi (or Zyrian, or Komi-Zyrian) has a much larger number of speakers then Nenets or Veps, with over 350 thousand speakers, mainly in the Komi Republic of northern Russia. This language is part of the Permic branch of the Finno-Ugrics and is closely related to the other member of that branch, Udmurt. Komi has several dialects with two main dialects. Komi-Zyrian is the largest of the dialects, spoken in the Komi Republic, and it is used as the main literary basis for that area. The second dialect, Komi-Yodzyak, is spoken in the southern parts of the Komi Republic as well as in a small area of Perm. Both dialects are closely related and mutually intelligible.  Trilingual (Russian, Zyrian and English) sign in a hotel in Ukhta, Komi Republic Komi has gone through quite a number of writing systems over the centuries. The writing system Komi first used was the Old Permic script, invented by a missionary in the 14th century. The alphabet seemed to be a mix of medieval Greek and Cyrillic. In the 16th century, this was replaced by the Russian alphabet with some modifications. In the 17th century, Komi adopted the Cyrillic alphabet then changed again in the 1920s with another modified Cyrillic alphabet, Molodtsov. It changed to the Latin alphabet in the 1930s, then in the next decade converted back to Cyrillic with a few extra letters. In it's current form, it has seven vowels. If a language could have an identity crisis (and some will argue they can), Komi would be a likely candidate for one. The Komi language is "definitely endangered", meaning children no longer learn the language as their mother tongue at home. In 1989, the First Komi National Congress established a Komi National Revival Committee, which managed to get Komi and Russian declared coequal state languages in the Komi Republic, but progress in reviving it beyond that has been limited. Commonality A common tie in the Finno-Ugric languages is the absence of grammatical gender, a trait shared with English. They also have a rich case system which can be daunting to first time learners. They are also normally agglutinative in nature, meaning words are comprise of morphemes attached together without many changes happening between them. Each of these morphemes has its own meaning, so a normal Finno-Ugric verb will consist of separate morphemes which relate the tense, aspect and agreement. Now you know more about the Finno-Ugric languages in general as well as about some lesser known members than probably did before. Next time one of your friends mentions he or she is learning Finnish or Hungarian, you can ask them if they have considered one of these other related languages. Then they can look at you as if you've grown a third head. |

| Languages in Peril - The Finno-Ugrics | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Writer: | Luke Delgado | |||||||||||||||||||

| Images: | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

All images are Copyright - CC BY-SA (Creative Commons Share Alike) by their respective owners, except for Petey, which is Public Domain (PD) or unless otherwise noted.

|

Looking for learning materials? Scriveremo Publishing, has lots of fun books and resource to help you learn a language. Click the link below to see our selection of books, availlable for over 30 langauges!

| |

comments powered by Disqus