Interesting Facts About Vurës

An Indigenous Language of Vanuatu

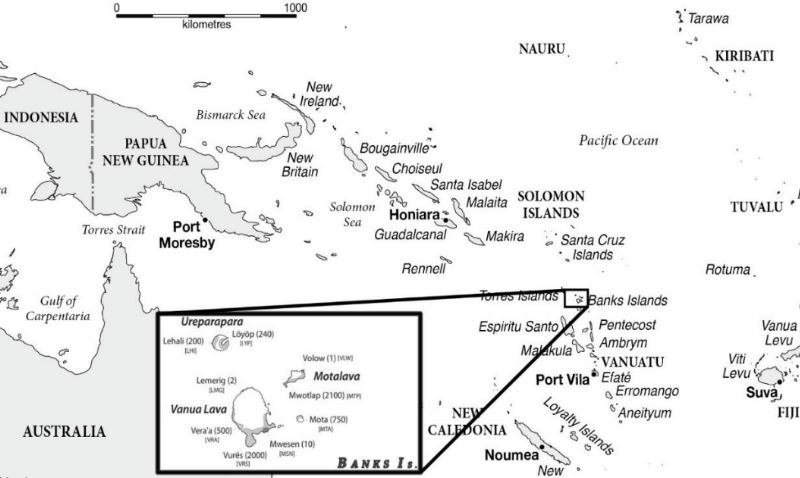

The small island country Vanuatu, located in the South Pacific Ocean between the Solomon Islands, Fiji, and New Caledonia, is home to almost 140 languages. All of these languages belong to the Oceanic branch of the Austronesian family. With a population of only 270.000 people on 83 islands, this country has the highest density of languages per capita in the world. That's a paradise for linguists, language enthusiasts, and polyglots! The people are called Ni-Vanuatu, or short Ni-Van, and they live a traditional life in harmony with nature. Most of the Ni-Van spend their lives working in the garden, cooking aelan kakae 'island food' for their families, doing community work in the church, or selling their produce in small local stores. While tourism is now a growing industry on the two most accessible islands Efate and Espiritu Santo, the northernmost Torres-Banks Islands see very few tourists. The biggest of these islands is called Vanua Lava or Vōnō Lav in the local language, which means 'big island'. I spent six weeks on this island living the traditional life with a local family to gather material for my doctoral research on the language called Vurës. About Vurës Vurës [βy.ˈɾœs] is the dominant language of Vanua Lava. The speakers call their language qaq ta ko 'language from here'. It is actively spoken by about 2,000 people and acquired as the first language by most of the children along a 14 kilometer stretch in the south of the island, spanning an area of about 54 km². The main settlement is Vētuboso [βɪ.t̪y.ˈmbɔ.sɔ], a fairly large village for local standards with a little over 600 people. Despite the small number of speakers, Vurës is not considered endangered, as it is the main means of communication between people of all ages in the community. However, the languages of instruction at school and in church are the creole language Bislama (the national language of Vanuatu) and English. Despite some efforts of previous researchers, the local school does not use educational material in Vurës, which means that nearly every speaker of Vurës is illiterate in their own language. Only very few settlers from other islands acquire Vurës well enough for daily communication, so inter-ethnic conversation usually takes places in Bislama. For the writing system of the language, I follow the orthography developed by Dr. Catriona Malau, as explained in her book A Grammar of Vurës, Vanuatu, published in 2016. How to get to the Vurës community Access to the village is not for the faint-hearted. To get to Vanua Lava, there are basically two options: By boat from another nearby island to Vureas Bay or to Sola, the commercial settlement of Vanua Lava, or by a small 19-passenger airplane from Luganville on Espiritu Santo to Sola Airport. Once arrived on the grassy landing strip in Sola in the east of the island, you collect your bag and start the long hike across the island to the west. This journey may take between four and six hours, depending on your fitness and the weather. You will be walking uphill, downhill, through fords and waist-deep torrents in the humid heat with little pedestrian traffic on your way. About half of the track is now sealed, the rest is gravel and mud. It is common to slip and fall into the rivers on the way, so any equipment should be stored securely in the bag. There is now a 4WD taxi service, which is very expensive for local standards, so consider the scenic walk along the coastline. To find the right track, it is always wise to have a local person by your side.  The main village Vētuboso lies on the west coast and consists of many hamlets, some of which are down at the shore while others are on an elevated plateau. Every researcher needs to meet Eli Field Malau at some point, the local fieldworker who is most knowledgeable about the languages on his island and around. I stayed with him and his family and called him Mam 'Daddy'. I called his wife Joana Leo Die 'Mum'. As such, I was adopted as their son into the Qön̄ clan. Later I stayed with my host brother Kali Malau and his family. They provided me with food every day and with my own house made from bamboo and local wood. Pronunciation Vurës has 15 consonants and 9 vowels. Most of these phonemes are not difficult to produce for English speakers and the orthography should be self-explanatory. But there are a handful of sounds that are not found in English or differ from their English spelling.

Note that the voiced stops b and d in Vurës are prenasalized and pronounced like mb (as in amber) and nd (as in candy), respectively. It is also important to know that diphthongs in Vurës are pronounced differently from English, so miat sounds like mee-utt, and die sounds like dee-yeah. Survival Phrases The first thing you learn when you stay with an indigenous community is what people talk about in their daily life. This is often quite different from western civilizations. Except for wishing each other a 'good day', it is very common to ask where someone has just come from and where they go to. This question is important and needs to be answered meaningfully. You can say that you come from the sea and go to the village, or you come from the village and go the sea. There are special words for 'seawards' and 'inland'. In some cases, you can specify the exact cardinal direction. For example, if you come from the sea but you walk all across the island, you might use 'eastwards' or 'other side'. Here are some examples:

Apart from these questions that you will encounter on the way through the village, many people also might want to know which vēnēm̄ 'clan' you belong to. The community has 18 such clans, which follow a matrilineal organization.

The following phrases are also very common in Vurës. Knowing them will get you around the island easily.

Numerals The numerals from 1-10 are actively used by all people. Anything beyond that is often replaced by Bislama numerals, which are shorter and easier. Some children are confused by the Vurës numeral system and do not even understand the higher numbers. The prefix ni- is used for all digits from 1-10, but not for the teens and tens.

The prefix ni- can be replaced by va(g)- means 'x times', for example vagtöl 'three times.' To express ordinal numbers, the prefix ni- is dropped and the suffix -ne is added: tölne 'third.' The word for 'first' has the unique form m̄ie.  Pronouns and Possession Vurës pronouns indicate whether one, two, three, or more people participate in the action and whether the listener is included or not. The following chart illustrates this:

These pronouns can all occur independently as the subject or object of a clause. For possessed nouns, there is an elaborate system in Vurës. The article for possessed nouns is na, replacing the default article o. Generally, body parts, kinship terms, and other inalienable things must be suffixed with one of the following pronominal suffixes. In the dual and plural, there are two options how to express possession, but in daily conversation the free forms are preferred.

The vowel of the possessed noun changes depending on the person. The following examples give an overview of this feature:

For alienable things, such as material belongings, domestic animals, plants, food, and abstract nouns, the language uses relational classifiers, which depend on the use of the possessed noun. The table below lists the most common of these classifiers:

When these classifiers are used in a possessive construction, then the order is relatively free and they can be used to indicate the various functions of an item, as shown here with qō 'pig':

Tense or Aspect? In Vurës, verbs do not change according to the tense, as it is done in English. The language uses aspect markers to achieve the same information. When something has happened before and it has an effect on the present, then the perfect aspect marker is used. When something is ongoing, will happen in the future, or happened continuously in the past, then the imperfective aspect marker is used. The negation replaces all these aspects markers. All these markers have different forms according to the vowel harmony, which depends on the following vowel.

When the aspect is irrelevant to the situation or when it is the same as in the preceding context, then the gnomic aspect marker is used. This marker does not follow the vowel harmony rule but has a different shape depending on the person it is used with.

How to say 'to have' and 'to be' In many European languages, the auxiliary verbs 'to have' and 'to be' are very common. However, in Vurës these do not exist. Instead of 'to have', you would say 'it is for someone' or 'someone's … exists'.

There is no way to express 'to be' in predicational expressions. Adjectives that are usually accompanied by the copula 'to be' in English, are most commonly verbs in Vurës.

This article is just a brief overview of some interesting facts about Vurës. If you have the chance to visit the island of Vanua Lava one day, you can now impress the locals with some basic phrases in their language. They'll surely invite you for a kava session or a scenic walk to one of the waterfalls nearby while you can keep practicing their language. If you've got questions about Vurës and other languages in northern Vanuatu, you can contact Daniel Krauße (daniel.krausse@uon.edu.au) or Dr. Catriona Malau (catriona.malau@newcastle.edu.au).  Daniel Krauße is a PhD Candidate in Linguistics at the University of Newcastle in Australia. In his doctorate program, he investigates the syntax and semantics of serial verb constructions in Vurës and coverb constructions in Wagiman. He received his BA and MA degree from the Goethe University of Frankfurt in Germany. Daniel specializes in Austronesian languages and the languages of Southeast Asia. His research interests include linguistic typology, historical linguistics, etymology, morphosyntax and writing systems. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Interesting Facts About Vurës: An Indigenous Language of Vanuatu | ||||

| Writer: | Daniel Krauße | |||

| Images: | ||||

| ||||

All images are Copyright - CC BY-SA (Creative Commons Share Alike) by their respective owners, except for Petey, which is Public Domain (PD) or unless otherwise noted.

comments powered by Disqus