Ferdinand de Saussure

Signs of Language

|

Theories Synchronic vs. Diachronic Linguistics Two ways of studying languages are synchronic and diachronic linguistics. Synchronic is the study of a language at a certain point. It looks at the way the language works at a particular point, like Shakespearean English. The English of that time is different from Modern English. Diachronic is the study of the changing state of language over time. That would compare the differences between Shakespearean English and Modern English, seeing how the first became the second. In a sense, it's looking at languages as an evolving being rather than a fixed entity. De Saussure brought about many changes in linguistic studies. He emphasized a synchronic view of linguistics in contrast to the earlier diachronic view. The synchronic view looks at the structure of language as a functioning system in whole at any given point of time. The diachronic view looks at the way a language develops and changes over time. This distinction was considered a breakthrough and became generally accepted. His work was wide ranging, and the three most predominant contributions are those dealing with Indo-European philology (Laryngal Theory), the relations between words and rules (Structuralism), and the combinations of "signs" in a language (Semiology). Laryngeal Theory In Saussure's first major publication, which dealt with Indo-European philology, he proposed the existence of "ghosts" in Proto-Indo-European (PIE) called "primate coefficients". The Scandinavian scholar Hermann Möller suggested that these might be laryngeal consonants, leading to what is now known as the laryngeal theory, and the sounds became known as "laryngeals". These consonants have mostly disappeared or have become identical with other sounds in the recorded Indo-European languages, so their former existence has had to be deduced primarily from their effects on neighbouring sounds. There were three such laryngeals: h1, the "neutral" laryngeal; h2, the "a-colouring" laryngeal; and h3, the "o-colouring" laryngeal. The theory did not begin to achieve any general acceptance until Hittite was discovered and deciphered in the mid-20th century. At that point, it became apparent that Hittite had phonemes (tiny sound units that help distinguish between utterances), for which the laryngeal theory was the best explanation. Nowadays, the existence of these sounds is widely accepted by philologists, mainly because proposing their existence helps explain some sound changes that appear in the language descendents of PIE. It is most likely that de Saussure's attempts to explain how he was able to make systematic and predictive hypotheses from known linguistic data to unknown linguistic data stimulated his development of structuralism. Structuralism De Saussure created two terms to define a way to look at language. The first, "parole", which is French for "speech", refers to the sounds that a person makes when speaking, or a graphic representation of that sound. The same paroles might exist in multiple languages, but have very different meanings. The second term, "langue", which is French for "language", refers to the system of conventions and rules that are applied to paroles, to make them understandable between people. As an example, the sound we make in English for "see" ([si:]), has multiple meanings in English: it is a verb meaning to visualize with an eye, a large body of water, and a letter of the alphabet. We understand its meaning by its context, which is part of the rules set up in the langue. Moreover, the same parole means "yes" or "if" in Italian, and is understood by the langue of that language. Speaking of linguistic law in general is like trying to pin down a ghost, or wrestle a gorilla. Both of these ideas are integral to the modern theory of structuralism. De Saussure put forth that a word's meaning is based less on the object it is referring to and more on its structure. That is, when a person selects a word, he does so in the context of having had the chance to choose other words. This idea adds another dimension to the chosen word's meaning, since humans normally instinctively base a word's meaning upon its difference from the other words which were not chosen. So the words we use are decided upon by our refining our meanings in a logical, structured fashion. De Saussure's theories on this subject laid down the foundations for the structuralist schools in both social theory and linguistics. His impact on the development of linguistic theory in the first half of the 20th century is huge. Two currents of thought came about independently of each other. In Europe, the most important work was being undertaken in the Prague School. Nikolay Trubetzkoy and Roman Jakobson headed the efforts of the Prague School in setting the course of phonological theory for the decades following 1940. Jakobson's universalizing structural-functional theory of primatology, which dealt with how primates developed languages, was the first successful solution of a plane of linguistic analysis, using the de Saussure's hypothesis. In the Copenhagen School, Louis Hjelmslev proposed new interpretations of linguistics from the structuralist theoretical framework. In America, de Saussure's ideas helped guide Leonard Bloomfield and the post-Bloomfieldian Structuralism practices. These influenced such researchers as Bernard Bloch, Charles Hockett, Eugene Nida, George L. Trager, Rulon S. Wells III, and through Zellig Harris, the young Noam Chomsky. This further influenced Chomsky's theory of Transformational grammar, as well as other contemporary developments of structuralism, such as Kenneth Pike's theory of tagmemics, Sidney Lamb's theory of stratificational grammar, and Michael Silverstein's work. Outside the field of linguistics, the principles and methods employed by structuralism were adopted by scholars such as Roland Barthes, Jacques Lacan, and Claude Lévi-Strauss, and were implemented in their various areas of study. However, their broad interpretations of de Saussure's theories, which already contained ambiguities, and their application of those theories to non-linguistic fields such as sociology and anthropology, led to some theoretical difficulties and proclamations of the end of structuralism in those studies. Semiology While de Saussure seems to have veered off the path established for him by his scientific relatives, he was and still is widely regarded as a scientist. His perception of linguistics as a branch of science he called semiology (the theory and study of signs and symbols) and through his teachings, he encouraged other linguists to view language not "as an organism developing of its own accord, but as a product of the collective mind of a linguistic community."

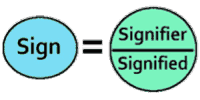

De Saussure's "Course in General Linguistics" laid out a notion that language may be analyzed as a formal system of different elements, which he referred to as "signs". Within a languages, these signs evolve constantly. A sign comprises of two parts: the signifier (what it sounds or looks like in vocal or graphic form) and the signified (the object the signifier represents). For example, a small object that can be held in the hand and holds a liquid for drinking would be the "signified" of the sound "cup", which would be the signifier. The relationship between the two parts of the sign, de Saussure postulated, is hazy and the parts may be impossible to separate because of their arbitrary relationship. There is no particular reason that the sound "cup" is applied to that particular object, as can be easily shown by looking at its name in other languages (tasse, cupán, filxhan, kop, bolli, cangkir). Moreover, because of this arbitrary nature of the relationship, signifiers can shift within a language over time. The meaning happens only when people agree that a certain sound combination indicates an object or idea. Then this agreement creates a "sign" for the object or idea. Without that, nothing has meaning. In language there are only differences, and no positive terms. We know what a cup is through its relationship to other things. It holds water, unlike a book, while a lake also holds water, but we can't hold that in our hands to drink from it. Our minds, therefore, develop concepts because of these relationships. When we form these relationships because of what other objects are not, we are forming negative relationships, known as "binary oppositions". Followers of Saussure have extended this two part structure of signs to a three part one, in which the signified is an idea or concept (like the idea of holding a liquid in an object) and the object itself is called the "referent". Despite his many and formidable contributions to the field of linguistics, de Saussure has been criticized for narrowing his studies to the social aspects of language, thereby omitting the ability of people to manipulate and create new meanings. However, his scientific approach to his examination of the nature of language has had impacts on a wide range of areas related to linguistics, including contemporary literary theory, deconstructionism (a theory of literary criticism that proposes that words can only refer to other words and which tries to show how statements about any words subvert their own meaning), and structuralism. Fan or critic, however, one must concede that Ferdinand de Saussure's contributions to his field as well as others were far reaching and revolutionary, and have influenced generations of scholars. | ||

|

WORKS

| ||

| Ferdinand de Saussure - Signs of Language | ||||||||||||

| Writer: | Sofia Ozols | |||||||||||

| Images: | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Sources: | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

All images are Copyright - CC BY-SA (Creative Commons Share Alike) by their respective owners, except for Petey, which is Public Domain (PD) or unless otherwise noted.

comments powered by Disqus