Revisited

Early Bardic Literature in Ireland

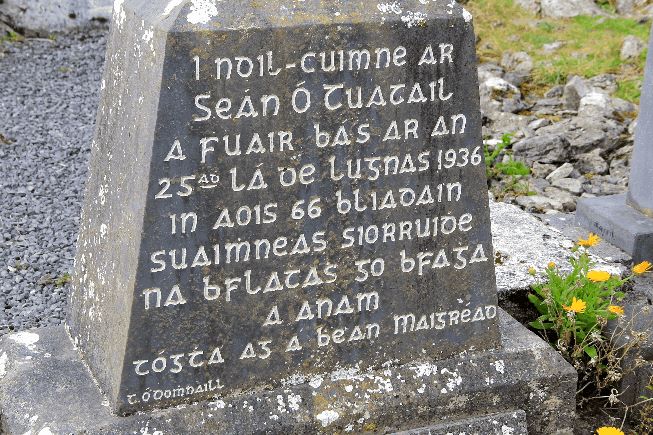

Ruins of a monastery or abbey The enthusiasm with which the Irish intellect seized upon the grand moral life of Christianity, and ideals so different from, and so hostile to, those of the heroic age, did not consume the traditions or destroy the pious and reverent spirit in which men still looked back upon those monuments of their own pagan teachers and kings, and the deep spirit of patriotism and affection with which the mind still clung to the old heroic age, whose types were warlike prowess, physical beauty, generosity, hospitality, love of family and nation, and all those noble attributes which constituted the heroic character as distinguished from the saintly. The Danish conquest, with its profound modification of Irish society, and consequent disruption of old habits and conditions of life, did not dissipate it; nor the more dangerous conquest of the Normans, with their own innate nobility of character, chivalrous daring, and continental grace and civilisation; nor the Elizabethan convulsions and systematic repression and destruction of all native phases of thought and feeling. Through all these storms, which successively assailed the heroic literature of ancient Ireland, it still held itself undestroyed. There were still found generous minds to shelter and shield the old tales and ballads, to feel the nobleness of that life of which they were the outcome, and to resolve that the soil of Ireland should not, so far as they had the power to prevent it, be denuded of its raiment of history and historic romance, or reduced again to primeval nakedness. The fruit of this persistency and unquenched love of country and its ancient traditions, is left to be enjoyed by us. There is not through the length and breadth of the country a conspicuous rath or barrow of which we cannot find the traditional history preserved in this ancient literature. The mounds of Tara, the great barrows along the shores of the Boyne, the raths of Slieve Mish, and Rathcrogan, and Teltown, the stone caiseals of Aran and Innishowen, and those that alone or in smaller groups stud the country over, are all, or nearly all, mentioned in this ancient literature, with the names and traditional histories of those over whom they were raised. There is one thing to be learned from all this, which is, that we, at least, should not suffer these ancient monuments to be destroyed, whose history has been thus so astonishingly preserved. The English farmer may tear down the barrow which is unfortunate enough to be situated within his bounds. Neither he nor his neighbours know or can tell anything about its ancient history; the removed earth will help to make his cattle fatter and improve his crops, the stones will be useful to pave his roads and build his fences, and the savant can enjoy the rest; but the Irish farmer and landlord should not do or suffer this.  Stone circle, perhaps once used as a place of worship The instinctive reverence of the peasantry has hitherto been a great preservative; but the spread of education has to a considerable extent impaired this kindly sentiment, and the progress of scientific farming, and the anxiety of the Royal Irish Academy to collect antiquarian trifles, have already led to the reckless destruction of too many. I think that no one who reads the first two volumes of this history would greatly care to bear a hand in the destruction of that tomb at Tara, in which long since his people laid the bones of Cuculain; and I think, too, that they would not like to destroy any other monument of the same age, when they know that the history of its occupant and its own name are preserved in the ancient literature, and that they may one day learn all that is to be known concerning it. I am sure that if the case were put fairly to the Irish landlords and country gentlemen, they would neither inflict nor permit this outrage upon the antiquities of their country. The Irish country gentleman prides himself on his love of trees, and entertains a very wholesome contempt for the mercantile boor who, on purchasing an old place, chops down the best timber for the market. And yet a tree, though cut down, may be replaced. One elm tree is as good as another, and the thinned wood, by proper treatment, will be as dense as ever; but the ancient mound, once carted away, can never be replaced any more. When the study of the Irish literary records is revived, as it certainly will be revived, the old history of each of these raths and cromlechs will be brought again into the light, and one new interest of a beautiful and edifying nature attached to the landscape, and affecting wholly for good the minds of our people.  Stone with Celtic writing on it Irishmen are often taunted with the fact that their history is yet unwritten, but that the Irish, as a nation, have been careless of their past is refuted by the facts which I have mentioned. A people who alone in Europe preserved, not in dry chronicles alone, but illuminated and adorned with all that fancy could suggest in ballad, and tale, and rude epic, the history of the mound-raising period, are not justly liable to this taunt. Until very modern times, history was the one absorbing pursuit of the Irish secular intellect, the delight of the noble, and the solace of the vile. At present, indeed, the apathy on this subject is, I believe, without parallel in the world. It would seem as if the Irish, extreme in all things, at one time thought of nothing but their history, and, at another, thought of everything but it. Unlike those who write on other subjects, the author of a work on Irish history has to labour simultaneously at a two-fold task - he has to create the interest to which he intends to address himself.  The ruins of an ancient sepulcher, or mausoleum, covered in moss The pre-Christian period of Irish history presents difficulties from which the corresponding period in the histories of other countries is free. The surrounding nations escape the difficulty by having nothing to record. The Irish historian is immersed in perplexity on account of the mass of material ready to his hand. The English have lost utterly all record of those centuries before which the Irish historian stands with dismay and hesitation, not through deficiency of materials, but through their excess. Had nought but the chronicles been preserved the task would have been simple. We would then have had merely to determine approximately the date of the introduction of letters, and allowing a margin on account of the bardic system and the commission of family and national history to the keeping of rhymed and alliterated verse, fix upon some reasonable point, and set down in order, the old successions of kings and the battles and other remarkable events. But in Irish history there remains, demanding treatment, that other immense mass of literature of an imaginative nature, illuminating with anecdote and tale the events and personages mentioned simply and without comment by the chronicler. It is this poetic literature which constitutes the stumbling-block, as it constitutes also the glory, of early Irish history, for it cannot be rejected and it cannot be retained. It cannot be rejected, because it contains historical matter which is consonant with and illuminates the dry lists of the chronologist, and it cannot be retained, for popular poetry is not history; and the task of distinguishing In such literature the fact from the fiction - where there is certainly fact and certainly fiction - is one of the most difficult to which the intellect can apply itself. That this difficulty has not been hitherto surmounted by Irish writers is no just reproach. For the last century, intellects of the highest attainments, trained and educated to the last degree, have been vainly endeavouring to solve a similar question in the far less copious and less varied heroic literature of Greece. Yet the labours of Wolfe, Grote, Mahaffy, Geddes, and Gladstone, have not been sufficient to set at rest the small question, whether it was one man or two or many who composed the Iliad and Odyssey, while the reality of the achievements of Achilles and even his existence might be denied or asserted by a scholar without general reproach. When this is the case with regard to the great heroes of the Iliad, I fancy it will be some time before the same problem will have been solved for the minor characters, and as it affects Thersites, or that eminent artist who dwelt at home in Hyla, being by far the most excellent of leather cutters. When, therefore, Greek still meets Greek in an interminable and apparently bloodless contest over the disputed body of the Iliad, and still no end appears, surely it would be madness for any one to sit down and gaily distinguish true from false in the immense and complex mass of the Irish bardic literature, having in his ears this century-lasting struggle over a single Greek poem and a single small phase of the pre-historic life of Hellas.  A panorama of the sea and the landscape leading to it In the Irish heroic literature, the presence or absence of the marvellous supplies no test whatsoever as to the general truth or falsehood of the tale in which they appear. The marvellous is supplied with greater abundance in the account of the battle of Clontarf, and the wars of the O'Briens with the Normans, than in the tale in which is described the foundation of Emain Macha by Kimbay. Exact-thinking, scientific France has not hesitated to paint the battles of Louis XIV. with similar hues; and England, though by no means fertile in angelic interpositions, delights to adorn the barren tracts of her more popular histories with apocryphal anecdotes.  Not so ancient. A bar on the paved streets of Dublin How then should this heroic literature of Ireland be treated in connection with the history of the country? The true method would certainly be to print it exactly as it is without excision or condensation. Immense it is, and immense it must remain. No men living, and no men to live, will ever so exhaust the meaning of any single tale as to render its publication unnecessary for the study of others. The order adopted should be that which the bards themselves deter mined, any other would be premature, and I think no other will ever take its place. At the commencement should stand the passage from the Book of Invasions, describing the occupation of the isle by Queen Keasair and her companions, and along with it every discoverable tale or poem dealing with this event and those characters. After that, all that remains of the cycle of which Partholan was the protagonist. Thirdly, all that relates to Nemeth and his sons, their wars with curt Kical the bow-legged, and all that relates to the Fomoroh of the Nemedian epoch, then first moving dimly in the forefront of our history. After that, the great Fir-bolgic cycle, a cycle janus-faced, looking on one side to the mythological period and the wars of the gods, and on the other, to the heroic, and more particularly to the Ultonian cycle. In the next place, the immense mass of bardic literature which treats of the Irish gods who, having conquered the Fir-bolgs, like the Greek gods of the age of gold dwelt visibly in the island until the coming of the Clan Milith, out of Spain. In the sixth, the Milesian invasion, and every accessible statement concerning the sons and kindred of Milesius. In the seventh, the disconnected tales dealing with those local heroes whose history is not connected with the great cycles, but who in the fasti fill the spaces between the divine period and the heroic. In the eighth, the heroic cycles, the Ultonian, the Temairian, and the Fenian, and after these the historic tales that, without forming cycles, accompany the course of history down to the extinction of Irish independence, and the transference to aliens of all the great sources of authority in the island. |

| Revisited - Early Bardic Literature in Ireland | ||||

| Writer: | Standish O'Grady | |||

| Images: | ||||

| ||||

| Sources: | ||||

| ||||

All images are Copyright - CC BY-SA (Creative Commons Share Alike) by their respective owners, except for Petey, which is Public Domain (PD) or unless otherwise noted.

comments powered by Disqus