Linear A & Linear B

Lost Minoan

|

As an adult, Ventris used Kober's clue to construct a series of grids, associating the symbols on the tablets with consonants and vowels. While he still could not determine which consonants and vowels they were, he learned enough the underlying structure of the language to begin guessing.

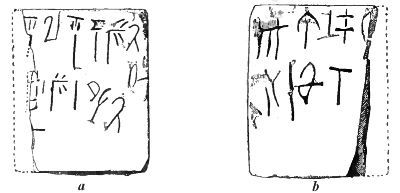

Pylos Linear B tablet, similar to those found at Knossos Other Linear B tablets had been discovered on the Greek mainland, and in comparison to those found at Knossos, there was reason to believe that some of the chains of symbols Ventris he had found on the Cretan tablets were names. Noting that certain names appeared only in the Cretan texts, he made an imaginative guess that those names applied to cities on the island. He then got lucky when one of the sets could only be one particular town, and no other. This insight proved to be correct. This allowed him to fill in the sounds of some of the signs, and he was able to unlock much of the text. It was finally determined that the underlying language of Linear B was in fact very old Greek, dating back some 500 years before Homer. This overruled Evans' original theories of Minoan history and established that Cretan civilization, at least in the later periods of the Linear B tablets, had been part of Mycenaean Greece. Linear B was completely deciphered in 1952. Hieroglyphics

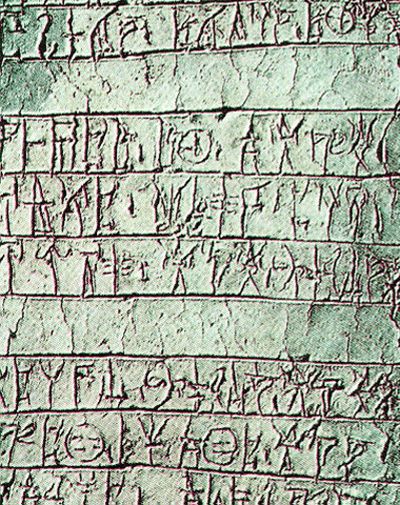

A sample of Egyptian hieroglyphics Hieroglyphics are a form of writing in which the letters/words are more picture-like, i.e. three waving lines running parallel to each other might denote "river". The hieroglyphics that were found at Knossos are samples of very old Cretan writing. This writing appeared mainly on clay seal stones. They depict physical objects to most probably record the quantities of these objects they protected. The normal progression of a hieroglyphic system is that is becomes stylized and linear. For example, quantities would come to be represented by numerals, instead of multiple impressions of the same sign. The pictures would become simplified, using lines to represent what were the more elaborate parts of the picture. Thus the term "linear" is used to describe the writing systems that evolved out of the hieroglyphics. Linear A Linear A is assumed to have been the evolution of the hieroglyphics at Knossos, and Linear B to be the progression from Linear A into the very ancient Greek. This assumption, however, has not been proven, or enabled either the hieroglyphics or Linear A to be deciphered. It is a syllabic (composed of signs to represent sounds, instead of letter groups forming sounds) script written from left to right, as is Linear B. The approximate phonetic values of many syllabic signs which are used in Linear A are also known from Linear B, but the language written in Linear A remains unknown and will probably remain obscure, since it doesn't seem to relate to any other surviving language in Europe or Western Asia.

Tablet of Linear A The most straight forward approach to deciphering Linear A may be to assume that the values of Linear A approximately match the values given to the fully transliterated Linear B script, and while this point of view has been of great interest to archaeologists, there is currently no linguistic grounds for accepting it. For the 213 Linear A signs, the majority have no link with any Linear B sign, and most of the similar signs have a small difference, which suggests a phonetic change. Theories Many scholars have put forth their own possible decipherments of Linear over the decades, and while many have strong merits, they also contain limitations. No one has been able to definitively prove what Linear A, or even what it might be related to. Semitic Origin Dr. Cyrus H. Gordon was an American scholar of Near Eastern cultures and ancient languages who also took an interest in decoding Linear A. Some of his own work included drawing connections between the Greek and Hebrew civilizations. Using this work, his knowledge of semitic languages, and even cryptology (which he did while serving in the U.S. Army in WWII), Dr. Gordon suggested that Linea A was a semitic language, which the Bible called Hamitic, and his first article suggesting this was published in 1957. However, there is little evidence to support this connection, and while most scripts used to represent Semitic languages have few vowels, Linear A has many. Luwian Luwian is an extinct language of the Anatolian branch of the Indo-European language family. It is closely related to Hittite and was among the languages spoken by people in Arzawa, later known as Lydia, in what is now Turkey. During the 1960s, a theory evolved that Linear A could be an Anatolian language, close to Luwian, based upon the phonetic values of Linear B. This theory, however, lost many supporters during the second half of the 20th century due to the growth of archaeological and linguistic data about the Anatolian languages and peoples. In 1997, Gareth Alun Owens, a British-Greek academic, published a collection of essays titled "Kritika Daidalika", which support the view that Linear A might represent an archaic relative of Luwian. He based this assertion on the possible Indo-European but non-Greek roots of a small number of words that were readable read by using the known Linear B or Cypriot sound values of certain Linear A signs. During the 1960s, a theory evolved that Linear A could be an Anatolian language, close to Luwian, based upon the phonetic values of Linear B. Owens postulated that the phonetic values of 90% of the Linear A characters correspond to those of Linear B figures of similar appearance. Ten characters do not match, and their meaning can only be speculated upon. Using his system of correspondences, Owens uncovered several place names which appear in the Linear B tablets and figure prominently in the archaeological history of Crete. He also put forth that he had found evidence of grammatical gender for nouns, as well as vocabulary and noun and verb endings that to indicated the basic "Minoan" language of the Linear A tablets to be an Indo-European language of the Satem branch. The drawbacks to this theory include that there is no remarkable resemblance between Minoan and Hitto-Luwian morphology, no existing theories support the migration of the Hitto-Luwian peoples to Crete, and the obvious anthropological differences between Hitto-Luwians and the Minoans, as mentioned before. Phoenician Phoenician is a semitic language originally spoken in what is now known as Lebanon, parts of Syria, and parts of the Mediterranean coast. Working from Gordon's theories that Linear A might be a Semitic language, scholar Jan Best published an article entitled "The First Inscription in Punic — Vowel Differences in Linear A and B" in 1991. In it, Best claimed to demonstrate how and why Linear A notates an archaic form of Phoenician. However, for many of the same reasons, his theory drew widespread criticism. While there are a few terms the may be of Semitic origin, there simply isn't enough evidence to make the link. Indo-Iranian Hubert La Marle, a French researcher in linguistics and epigraphy, started studying Linear in 1989, and developed his own theory that it may belong to the Indo-Iranian family of languages. This theory is based largely on the frequencies of each sign in certain positions. He also compares Linear A to other ancient scripts around the eastern Mediterranean. He suggests that these two methods provide many conclusions about the phonetic nature of the syllabic signs for a most of the signs, and that aspects of Linear A closely resemble ancient Indo-Iranian.

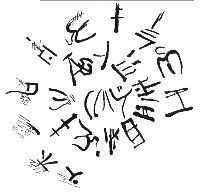

Linear A. Copy of inscriptions round the inner surface of cup Furthermore, La Marle's study includes a coherent presentation of the morphology of the language. It avoids the complete identification of phonetic values between Linear A and B. However, his critics have pointed out a few problems with this theory. First, it uses frequencies of signs, rather than their structure within Linear A, to make a translation. He also assigns phonetic values to the signs based on superficial resemblances to signs in other scripts, as opposed to direct matches. While differences in signs can occur over time, it is not a good basis for determining connections. Some scholars also contend that the work is biased, because he attempts to translate the words into a language he has chosen, rather then matching a language to the translation. Conclusion

Knossos north entrance rebuilt Work continues on the decipherment of Linear A texts, and there may yet be a discovery in the future that helps clarify the meaning of the language. It may as yet be somehow connected to Linear B, or connected to a currently existing language, as in the theories above. It is also possible, however, that the language was separated long ago from any language we know and a connection will never be made. Despite that, much has been learned about the Minoan civilization through the study of the artifacts inscribed in Linear A. Linear B has also been instrumental in explaining the historical connection between the Minoans and Greeks. Both scripts have also been used in analyzing other linguistic artifacts, and it as yet possible that someone might one day find another "Rosetta Stone" to help solve the mystery. |

| Linear A & B - Lost Minoan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Writer: | Lucy Martin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Images: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All images are Copyright - CC BY-SA (Creative Commons Share Alike) by their respective owners, except for Petey, which is Public Domain (PD) or unless otherwise noted.

comments powered by Disqus