Motivation

Expressing oneself and the expression of oneself in language learning

|

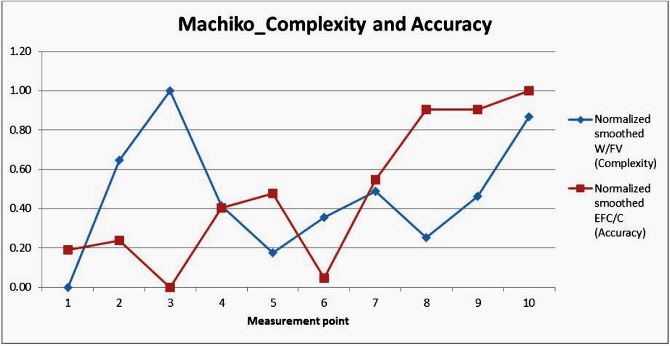

A quick exercise Before I get into the topic, if you are currently learning a language, I would like to invite you to study the next two graphs. I suggest you draw them on a sheet (no need to be too precise!).  Graph 1. Year Trajectory Look at the one entitled "Year trajectory" and think back over the last year how motivated you were to learn your second language. When have you felt periods of high or low motivation? What was going on in your life? Children, marriage, divorce, parents passing away, promotion at work, winning the lottery? The other graph, entitled 2 hour trajectory, is for next time you settle to do some language learning: track the level of your motivation from 1 to 10 every ten minutes. When you finished your hour or two of learning, look at the line. How linear is it?  Graph 2. 2 hour trajectory It may be possible that over the last year you saw yourself as a very motivated learner, but in the completion of exercises your motivational trajectory was U shaped, downwards, or up and down. If you are a teacher, you may be familiar with sociocultural theory, and particularly the relationship between goals and actions and between motives and activity. Without going into too much detail, the first graph would be a representation of how your motives inspired your language learning, whereas the second graph shows how your immediate goals (becoming more familiar with a specific grammar question) inspires your action (completion of a single exercise). Within this sociocultural theory, motivation is found when goals and motives align themselves for the achievement of actions and activity. The purpose of this exercise is to show you the extreme variability of motivation both at macro an microlevels. Now imagine you are in a class of 20 learners, and now you can begin to imagine how many different motivational trajectories exist within that single microcosm, and that those motivational levels are not disconnected or discreet entities but form a very large motivational continuum from the shortest of actions to the entire length of your life. This article is divided into three sections: the first is a summary of motivational research, so that you can understand where it all started and where we are now. I will not go into every theory proposed, will only focus on the most important concepts. The second section will highlight some essential truth about our learning process. While not directly related to motivation, this section explains how we learn in a non-linear fashion, and that periods of regression are normal. Oddly, regression can even be seen as a positive sign! Finally, I will make a few suggestions to harness your or your student's motivation. Overall, I hope to give you some insights into the connections between who you are as a person and your drive to learn, and what you can expect in your journey. Introduction  Trying to establish a model for motivation is very difficult It makes intuitive sense that motivation is an important factor in the success of any language learning venture. Yet motivation in second language learning, an extensively researched concept, remains difficult to define. Robert Gardner, arguably the most celebrated author in motivation literature, and one of two authors who introduced motivation as a focus for systematic research, admitted that it was not really possible to give an accurate definition of the term. Instead, he offered a description of motivation as a process. He stated that motivation was "the extent to which the individual works or strives to learn the language because of a desire to do so and the satisfaction experienced in this activity. Effort alone does not signify motivation... When the desire to achieve the goal and favourable attitudes toward the goal are linked with the effort or the drive, then we have a motivated organism" (R. C. Gardner, 1985, pp.10-11, fig.1). One of the most motivating things about learning a language is getting to the point where you can have a conversation with a native speaker, during which they do not need to slow down or adapt their language. According to Gardner, motivational orientations could be seen as fitting on a continuum. At one end stood integrativeness, where learners were interested in learning a language in order to identify with the community of those speakers. At the other end was instrumentality, an orientation that motivated language learning for professional benefits or financial gains. Integrativeness is still impacting research more than 50 years after the concept was proposed. In Gardner's view, this was the orientation that led to a more likely successful outcome. Gardner's model did come under heavy criticism, not least because the population he was studying benefitted from particular circumstances which are not repeated in many other places. Indeed, he focused on the learning patterns of English speaking Canadians, who were acquiring French. Their easy access to native speakers and the relative harmonious cohabitation between the two ethnic groups made the conditions particularly propitious for integrative orientations to develop. Scholars highlighted that the learning context played a major part in how a learner related to the object of learning. Dimensions of complexity were added to Gardner's integration-instrumental continuum: time frames, feared outcomes, learner identity and cultural contexts were gradually conceptualised within the theory.  Using a language in a real world situation is a great motivator for learners For many academics, including myself, motivation is nowadays seen as an expression of identity. This is because the motivational process is understood as the dynamic interaction of a person's possible selves (their idea of who they could become) and their learning experience. The implication is that for learners to really engage with the language, they need to imagine themselves speak it, be part of a community of speakers, use the language in a way consistent with their personal, social and professional aspirations. The key question, the challenge for teachers is what can be done to get students to see how the language they are learning is relevant to their lives and how they may imagine themselves evolve in a real language context, as opposed to the classroom bubble. Here are three things I believe teachers and students would benefit from keeping in mind: how we learn, what makes the learner identify with the language and how imagination can help you. Section I: The learning trajectory Because what we are talking about here is motivation to engage in learning a language, it pays to have a look at how we learn. So, this is how we don't learn.  Graph 3. Linear learning progress If you have children, think about pretty much any development your little ‘un had to go through. I am sure you will remember toilet training, the stage my son is at currently. It's going great for a few days or a week or two, then one day it's like they have never been acquainted with a potty. The trajectory of learning a language is remarkably similar to that of potty training, possibly with as many tears. What is difficult to accept for a learner (and for teachers) is that the learning experience includes progression as well as regressions in all areas. Learning trajectories have a terrible tendency to be not only unpredictable but also co-dependant. For example, you will all have noticed that if you want to be more accurate in your second language (or in your first!), you are often less fluent, more hesitant. It's also been shown that grammatical complexity increases until the learner becomes fluent enough to express subtle meaning variations without having to rely on longer sentences! Here is for example a learner's development of complexity and accuracy. This graph shows the written accuracy and complexity development.  Graph 4. Foreign academic complexity and accuracy development (Rosmawati, 2014) Notice how accuracy has a tendency to drop when complexity increases, until the latter development stages. This is an indication that the student has acquired the complexity to the point that they do not need to compromise on their accuracy. If you are ready to accept both progressions and regressions, you are hopefully less likely to feel discouraged during your learning journey. When you notice regressions, despite your continued efforts, take them as a positive sign of your development! Because this means that there are other areas in which you are making crucial progress. |

| Motivation: Expressing oneself and the expression of oneself in language learning | ||||||

| Writer: | Olivier Elzingre | |||||

| Images: | ||||||

| ||||||

| Sources: | ||||||

| ||||||

All images are Copyright - CC BY-SA (Creative Commons Share Alike) by their respective owners, except for Petey, which is Public Domain (PD) or unless otherwise noted.

comments powered by Disqus