Google Translate Exposed:

The Truth Behind Everyone's Favorite Translator

|

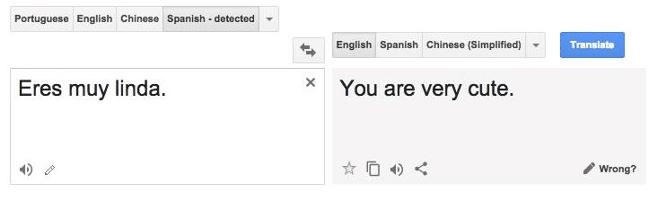

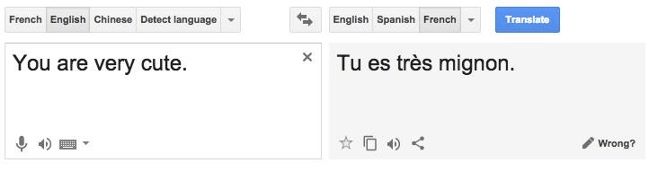

Nobody would argue that Google Translate is perfect: machine-generated translations are notorious for missing the mark, often laughably so. Still, with over 200 million translations performed each day in over 90 languages from Albanian to Zulu, Google Translate has come a long way since its humble beginnings, and is by far the most widely used translation service in the world. But how exactly does Google Translate work? As it turns out, the process isn't as straightforward as you might expect, and is the reason for some of Google Translate's successes, as well as its failures. At first glance, one might expect that Google Translate would simply compile dictionaries of many different languages, and translate equivalent words from each one. However, as any language learner knows, translating literally or word-for-word will result in a nearly incomprehensible end result. Realizing this, the folks at Google base their translations not in dictionary entries, but in real texts that have already been translated by humans. Google Translate's library is vast: it includes every European Union document since 1957 (all of which are professionally translated into over 20 languages), records from international companies that have been translated into multiple languages and uploaded onto the Internet, as well as thousands of articles and books that have surfaced on the web. Google Translate then translates novel text by scouring this enormous database and finding the most common translation for a given word or phrase. Therefore, Google Translate's output is based on human-created professional translations, effectively avoiding the aforementioned issues involving literal or word-for-word translations. For example, if you seek to translate "How are you doing?" from French into English, Google will find several real-life translations in its enormous database, and select the most common choice. So if you've ever entered something into Google Translate and been surprised by how accurate the translation was, this is why. However, this approach isn't without its shortcomings. Specifically, relying on existing translations may provide ample material for some language pairs, but not others. For example, there are abundant translations from French to English, but markedly fewer translations from French to Japanese. So, then, what happens when you want to translate a text from French to Japanese, and Google can't find enough existing material to provide a direct translation? When this happens, Google uses an intermediary step that has matches in both the source language (in this case, Spanish) and the target language (Japanese). Given the ubiquity of English as a worldwide lingua franca, this intermediary step is almost always English. So what does this mean for our Spanish-Japanese translation? Unable to find direct matches from Spanish to Japanese, Google will first translate the text into English, and will then further translate this new English text into Japanese. In other words, it involves two translation iterations instead of one. You might be asking if this is necessarily a bad thing. If the translation from Spanish to English is good, and the translation from English to Japanese is good, what's the problem? Well, on a basic level, think of the popular game "Telephone". No matter how hard everyone tries to accurately replicate the original message, after several iterations, it ends up getting distorted. In this sense, Google Translate's multiple iterations of translation is similar to playing "Telephone". But let's look at this more specifically. Say we have a simple Spanish-language sentence: Eres muy linda. This translates to "You're very cute", and Google translate correctly produces this, as we see below.  Importantly, however, Spanish adjectives inflect for gender. Whereas linda is used to describe women, lindo is used to describe men. Because of this, the above sentence is necessarily being spoken to a woman. However, given that adjectives in English do not inflect for gender, Google translate failed to capture this difference. As a result, see what happens when we translate this text from English to French:  Unfortunately, this is not the same as our original sentence. Indeed, mignon does mean "cute", but it is used to describe men; mignonne is used for women. Therefore, in its English translation, Google Translate lost track of the fact that the original sentence was directed towards a woman. The nuance was lost. Aside from showing that it's dangerous to use Google Translate to flirt in a foreign language, this example illustrates the problem of using English as an intermediary step when translating between two other languages. In doing so, we impose English-language grammar on the original text, and then use that as the basis to come up with a final translation. But English, like any other language, does not have every single conceivable grammatical feature (such as inflecting adjectives for gender). As a result, we necessarily lose some grammatical nuance if we use English as an in-between for our original and target texts. So, is Google Translate bad? No – it's great for getting the general meaning for a text you don't understand, and sometimes, it can provide really authentic translations. But it certainly can't replace the human touch – and especially when it uses other languages as intermediary steps. Thus, if you want a really good translation, don't look to Google: a trained, human professional is a much better choice. Or – even better – learn the language yourself, and become your own translator. Paul is an English teacher who lives in Argentina. Paul writes on behalf of Language Trainers, a language teaching service which offers foreign-language level tests as well as other free language-learning resources on their website. Check out their Facebook page or send an email to paul@languagetrainers.com for more information. |

| Google Translate Exposed: The Truth Behind Everyone's Favorite Translator | |||

| Writer: | Paul | ||

| Images: | |||

| |||

All images are Copyright - CC BY-SA (Creative Commons Share Alike) by their respective owners, except for Petey, which is Public Domain (PD) or unless otherwise noted.

comments powered by Disqus