The Secret Life of Diacritics

|

For those of us who have grown up with English as our native language, we are very comfortable with our Latin alphabet. It is composed of 26 letters, 5 of which are vowels and the rest of which are consonants. Nothing tricky about it. Well, at least when dealing with most of our English words. However, languages quite often "borrow" vocabulary from other languages, and those foreign words sometimes introduce strange spellings or even new characters. For example, most of us have probably eaten at a small food and beverage shop called a "café". This little restaurant gets its name from the French word "café", meaning "coffee" or "coffeehouse". According to English pronunciation, "cafe" should probably sound similar to "cape" or "cage", with the "a" being an "ay" sound and the "e" being silent. But instead, the word is pronounced "cah-FAY" (/ˈkæf.eɪ/), due to a little mark above the "e" which you probably mistook for a printing error the first time you saw it. Another French word we have adopted with this strange, altered letter is "fiancée" (or "fiancé", depending on if the person is male or female). This term is used to refer to a person who is engaged to the other, replacing the old fashioned "betrothed" for something more exotic sounding. French people, or anyone who has studied French, will of course recognise the acute mark. It changes the normal Latin "e" into a new sound without creating an entirely new letter. It is found in several languages using the Latin alphabet, including French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, Irish, Hungarian, Galician, Czech, Icelandic, Kashubian, Luxembourgish, Occitan, and Slovak. Oh, and in English, as we have seen, in certain adopted words or names, like Beyoncé.  A Street café in Berlin Some other English words you might have seen the acute mark used in are "cliché" and "risqué", both from French and both having their final silent letter converted into something new. This acute sign is part of a larger group of added markings called diacritics. A few of these words have been fully integrated with English and had their diacritics removed. One of those is "naive", which also comes from French where it is spelled "naïve". We have learned how to pronounce the word and, in order to keep spelling simple, removed the diacritic. "Café" is also in this process of naturalization, and you can often see it spelled just "cafe". This is what has happened to other words that were actually completely English but at one time were given diacritics to help in pronunciation. Words like hiätus, coöperative, daïs, and reëlect have dropped their markings to become hiatus, cooperative, dais, and reelect. Sometimes, hyphens are added (co-operative, re-elect) to make pronunciation clearer. Essentially, they can be seen as "patches" to software which is being upgraded. Each change introduces some problem which can be fixed by adding something else and establishing a new rule to cover it. In the word "naïve" and the words listed above is a different diacritic, called a diaeresis. Its function is also different from the acute. While the acute mark changed the sound of the vowel, the diaeresis is used to prevent a pair of vowels from being pronounced as a diphthong (a combination of vowels with a specific, single pronunciation). Normally in English, "ai" is likely to be pronounced as "ay", as in "afraid" or "fair". With the diaeresis, the vowels instead keep their own sounds and split the word into two syllables ("nah-EEV" /nɑˈiv/). French isn't the only language to give English words with diacritics. If you are into spicy food, you have probably tasted a jalapeño pepper, or maybe as a kid you attended a party with a piñata. Both these words come from Spanish and have a cute little squiggle over the "n" called a tilde. This modifies the sound of the "n" to have an extra nasalized component, like there was a "y" after it, similar to the way "n" is pronounced in "onion" and "dominion". Orthography First, it should be noted that having diacritics is not actually related to a language, since they denote sound in a writing system. Diacritics are part of the orthography, and for each language, it is possible to devise a writing system that includes all the sounds without the need for extra marks. But changing the writing system might not even be necessary, since the spelling of the words could simply be modified most of the time. Looking back at some of the words we introduced (café, fiancée, naïve, piñata) these could be spelled to show the correct sounds as cafay, fiansay, nigheve, and pinyata. These might look awkward to our brains, but remember that Old English had a very similar look. Second, sometimes the term "accent" is used instead of "diacritic", but it is important to realize that diacritics are used to denote many pronunciation changes, not just accent. History  Children swinging at a piñata, a word and tradition taken from the Spanish The word "diacritic" comes from the Greek word "διακριτικός" (diakritikós), meaning "distinguishing". These marks are used to show that a letter should be treated differently from the normal usage. That change can affect stress, short and long sound, or create an entirely new sound. So why do some languages have them and some don't? English only has them from adopted words or specific names, while many other languages which also use the Latin alphabet use many of these notations. Unfortunately, that is not an easy answer. Languages based upon Latin and using the Latin alphabet added in these modifiers as their spoken language developed. Latin itself uses no diacritics. The very first diacritics were introduced in Ancient Greece and Rome. They evolved and spread to later European languages for two main purposes. First, they helped define the pronunciations of letters and words, expanding the existing writing system without the need to add more letters. They also saved space when writing, which became very important as, during the early middle ages, when writing became more popular, ink and paper were expensive. We have already seen an example of this in the word "piñata". It was originally spelled "pinnata", but to save space (and thus money), Spanish scholars invented the tilde to indicate the letter was doubled. Looking at French, we know that the spelling of words is mostly based on the way they were pronounced in Old French (1100-1200 AD). However, since then the spoken language has continued to evolve, so that the spellings no longer match. Some of these changes have led to letters becoming silent in many words (ballet, faux) and multiple homophones (air, aire, ère, erre, ers, haire, hère). To accommodate for the changing sounds, diacritics were introduced. Essentially, they can be seen as "patches" to software which is being upgraded. Each change introduces some problem which can be fixed by adding something else and establishing a new rule to cover it. France has a particularly interesting history regarding the accent (`), or grave, mark. It is the same as the acute (´) mark, but it faces the other direction. In 1653, L’academie Francaise was established to protect and promote the French language, and one of the decisions they made was to introduce the usage of grave marks. What makes that so interesting is that they did this not to make spelling simpler, but to actually make it more complex. The reason was that they wished to distinguish between the educated and the ignorant. The elite would use the spellings with the extra markings to set themselves above others. This is similar to the practice of using calligraphy or very formal writing for documents of high importance. |

|

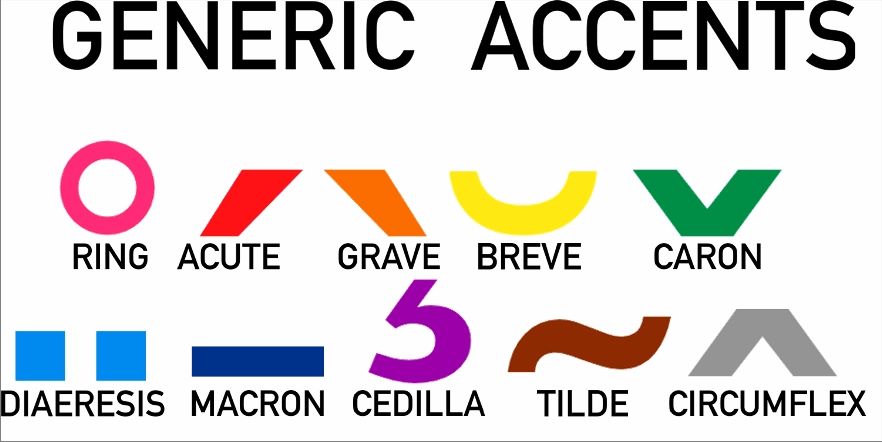

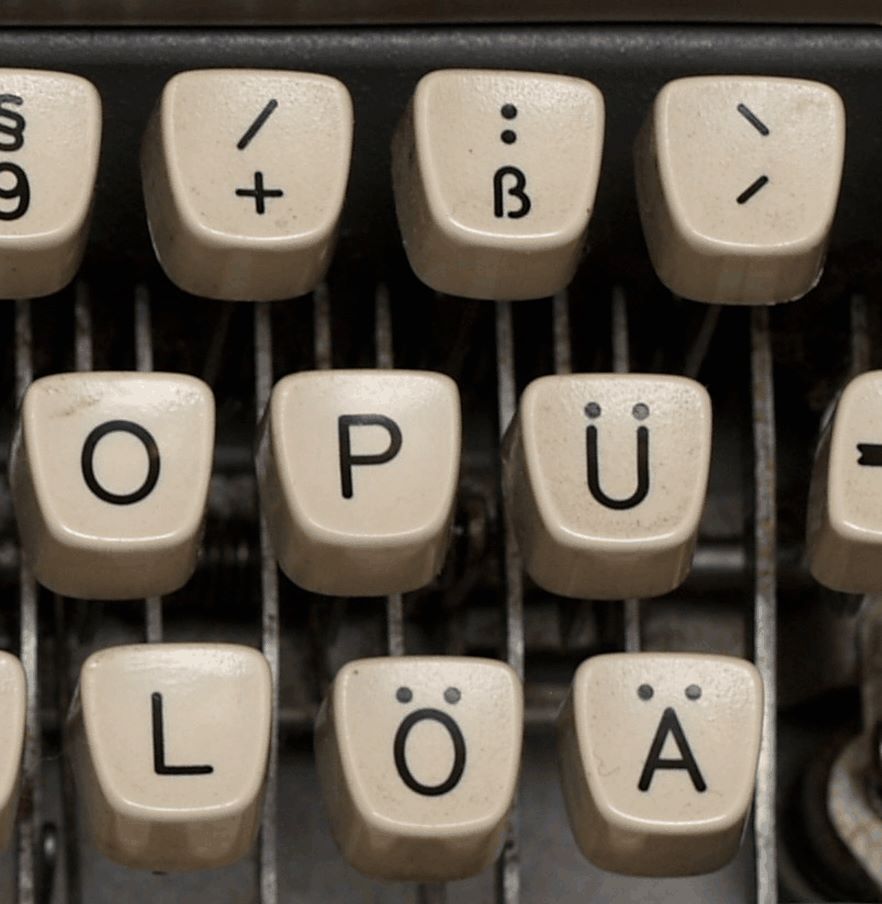

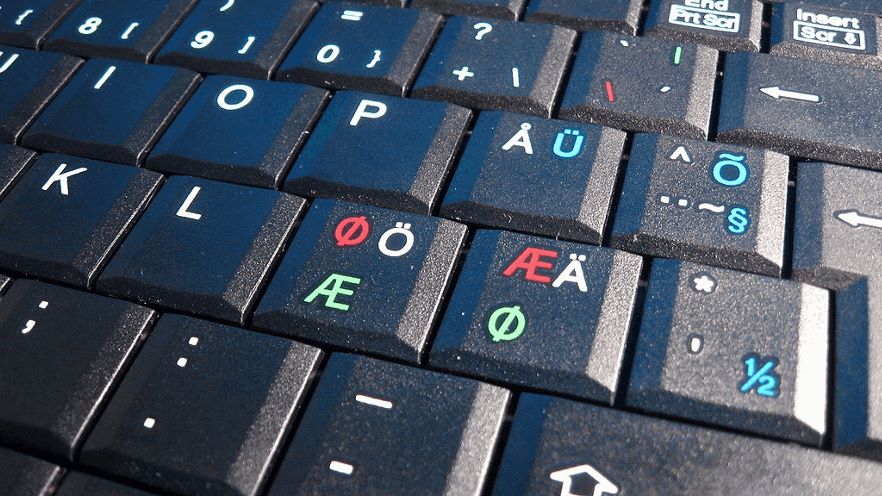

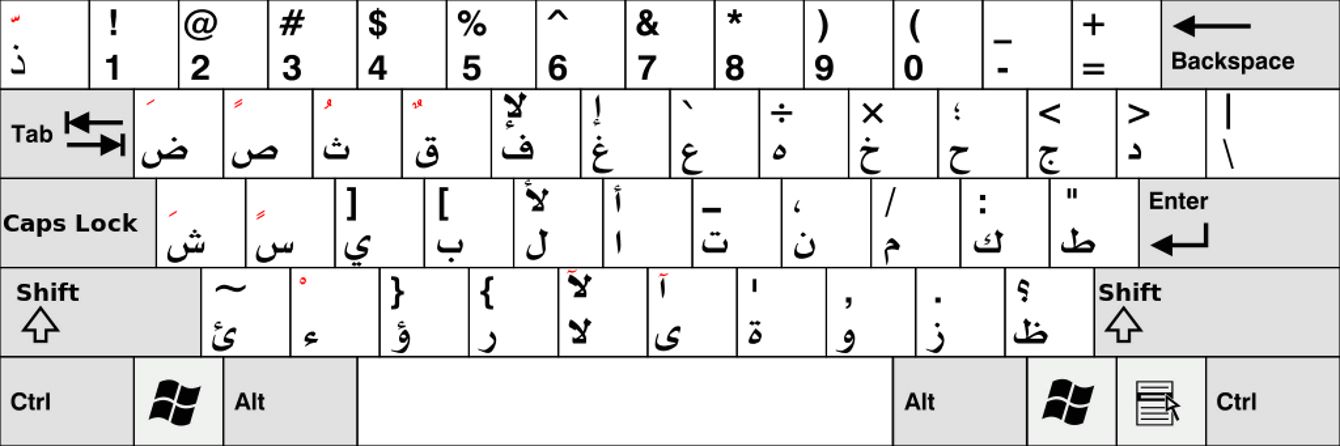

Usage Now it is time to look at the various forms. We have already looked at the acute, grave, diaresis, and tilde marks. These and others exist in numerous languages, sometimes for different purposes. It is also important to note that in some languages, letters with diacritics are considered to be completely unique characters while in others, diacritics are just additions to letters, and the letters with and without them are not considered to be different letters, just handled differently. French  Some of the most popular diacritics The usual diacritic marks in French are the acute, the grave, the circumflex, the diaeresis, and the cedilla. The acute over an "e" changes it to a longer sounding "ay" sound. The grave mark over vowels (à, è, ù) does one of two things. Over "a" or "u", it distinguishes between homophones: à vs. a, ou vs. où. When it is with an "e", it represents the sound of /ɛ/, or "eh". As we saw already, the diaeresis shows that a vowel combination should be broken up, not spoken as a diphthong. The letter with this mark must be pronounced separately, and it usually appears as ë, ï, ü, and ÿ. The circumflex looks like a little triangle without a bottom, and as a single mark, it is called a "carat". Over the vowels "a", "e" and "o" (â, ê, ô), it changes these sounds to /ɑ/ ("ah"), /ɛ/ ("eh") and /o/ ("oh"). It is also sometimes used to distinguish between homophones. It may also appear on "i" and "u" (î, û), but since the 1990 orthographic changes to the language, most of those occurrences have been dropped. The cedilla is a diacritic that appears under a letter instead of over it. It is also the only diacritic in French that is used on a consonant instead of a vowel. It appears under the letter "c", creating ç and being pronounced as "s" before the vowels "a", "o", and "u", where it would normally be pronounced as "k". It is not needed before "e", "i", or "y" because a "c" used before those always adopts the soft "s" sound automatically. Similar to English, the tilde only appears in French over "n" in words adopted from Spanish. Spanish  Part of a German 1964 Olympia typewriter showing the placement umlauts Compared to French, diacritics in Spanish are fewer and easier. The grave mark is used over vowels (á, é, í, ó, ú) to mark stress (la canción [song], también [also]) or to differentiate between homophones (sí [yes], si [if]). The tilde is used on the "n" to change that letter's sound. The diaeresis is also used in Spanish, but only over the "u" (ü) and only before "e" or "i". Normally, when "g" and "u" are used together before a hard vowel, both "u" and the vowel are pronounced, with the "u" sounding like an English "w" (guasón, guapo). To make the "u" have the "w" pronunciation when it is in front of a soft vowel, the diaeresis is added (lingüística, pingüino). More specifically, the diaeresis in Spanish forces two vowels to be pronounced as a diphthong. This is exactly the opposite way it is used in French and English, where it is used to separate diphthongs. German  Faroese sign with diacritics So it seems that diacritics can have different usages for the same marks. If you are at all familiar with German, you have probably also made the observation that the same character can have different names, for the two dot mark we have been calling a "diaeresis" is referred to as an umlaut for German, and it has a third usage. The umlaut appears over three vowels in German (ä, ö, ü) and is used to represent frontalization, which is placing an "e" after the vowel, similar to how English adds a silent "e" to the end of words to make the vowels long. German printers created the umlaut to save on printing. They were originally two small vertical dashes, but those got truncated into dots, thus the similarity with the diaeresis There is another shortened form in German, compressing "ss" into a single letter, ß, called "eszett". This is a ligature (a combination of two or more characters into a single glyph) and is viewed as a separate letter, while the umlaut is considered an addition; ä, ö, and ü are not considered separate characters. Since the spelling reforms of 1996, eszett is in the process of being phased out. Italian The Italian diacritics are mainly the acute and grave and used in the same way as Spanish - to denote stress or differences between homophones. There is a very rare usage of a circumflex (î) in old documents to represent a contraction of "ii". Nordic Languages Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish have a circle mark, called a ring over the letter "a", which may have once started as a diacritic but now makes "å" a distinct letter. Two of these languages also use various diacritics to differentiate between homophones: Danish has the acute mark and Norwegian uses the acute, grave, and circumflex (é, è, ê, ó, ò, â, and ô). The Swedish alphabet includes three letters with diacritics (å, ä and ö) which are treated as separate letters and appear at the end of the alphabet. They are used almost exclusively for loanwords from German and French. Baltic Languages  A laptop keyboard with Scandinavian characters containing diacritics Latvian has the several diacritics which have been added to existing Latin letters to form eleven entirely new ones. The names of these diacritics are the macron (ā, ē, ī, ū), the caron (č, š, ž), and the cedilla (ģ ķ, ļ, ņ). The macron, which looks like a bar or hyphen, is normally used to make a pronunciation long. The caron, which looks like an inverted circumflex, is normally used to palatize a letter (give it a sharper sound which is created by pressing the tongue to the palate, or roof of the mouth). The cedilla, which we have seen already in French, is mainly used to soften a sound. Note that the cedilla appears above the "g" in Latvian. Lithuanian also has the caron letters of Latvian (č, š and ž) and the macron (ū) acting as unique letters. It also includes the dot, or overdot, (ė), which gives the "e" a closed sound. Another new mark is the ogonek (ą, ę, į and ų), which looks like a reversed cedilla and has the effect of giving a nasalized pronunciation. As in Latvian, these letters with diacritics are considered to be unique letters. Other Diacritics and Languages There are far more examples of diacritics in the languages using the Latin alphabet - too many to cover in this single article. These include diaeresis, tilde, acute, grave, circumflex, caron, overdot, macron, overring, cedilla, ogonek, double acute, double grave, triangular colon, underbar, slash, crossbar, breve, sicilicus, titlo, apostrophe, hoi, horn, undercomma, double breve, tie bar, double circumflex, longum, and double tilde. These are used, both as additions to letters or in forming unique letters, in a variety of languages, including Afrikaans, Albanian, Asturian, Aymara, Azerbaijani, Belarusian, Bengali, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Catalan, Cornish, Crimean Tatar, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, Esperanto, Estonian, Faroese, Filipino, Finnish, Gagauz, Galician, Hawaiian, Hebrew, Hungarian, Icelandic, Irish, Kurdish, Lakota, Latvian, Leonese, Lithuanian, Livonian, Macedonian, Maltese, Manx, Norwegian, Occitan, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Scottish Gaelic, Serbian, Slovak, Slovene, Swedish, Tamil, Thai, Turkish, Turkmen, Ukrainian, Vietnamese, and Welsh. While we have been looking at how diacritics are used to modify letters of the Latin alphabet, there are also various markings in other languages and alphabets, including Arabic, Chinese, Greek, Hebrew, and Korean. Are Diacritics Needed?  Arabic keyboard layout, capable of adding harakat diacritics Some people now question if languages still need to use diacritics. As we have seen already, with the examples in English, people can learn how to pronounce the words properly without extra marks guiding them. How often do you still see "cafe" with the acute mark? "Naive" has completely lost its diaeresis We also have unlimited capacity for printing, so using them to save space is no longer required, as we have seen with the German eszett being phased out. The other part of this argument is that it is harder to use the diacritics in print because so much is done on computers and it then requires specialized keyboards, popup menus for extra characters, or multiple keystrokes to insert a single character. Lastly, it is possible to distinguish between words that are spelled the same without diacritics just by the contexts. No one thinks "I will lead you there" has anything to do with the metal. Would removing the acute from "sí" really make people think you saying "If, I would like some tea"? With some reforms already changing spelling rules to remove them, as well as natural language evolution, it is possible that we will someday have diacritic free writing systems again? I hope this peek into the world of diacritics will help make you aware of the importance of these little characters and understand their importance in the language world. |

| The Secret Life of Diacritics | ||||||||||

| Writer: | Erik Zidowecki | |||||||||

| Images: | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Sources: | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

All images are Copyright - CC BY-SA (Creative Commons Share Alike) by their respective owners, except for Petey, which is Public Domain (PD) or unless otherwise noted.

|

Looking for learning materials? Scriveremo Publishing, has lots of fun books and resource to help you learn a language. Click the link below to see our selection of books, availlable for over 30 langauges!

| |

comments powered by Disqus