How Do You Say It?

A look at sound notation systems

|

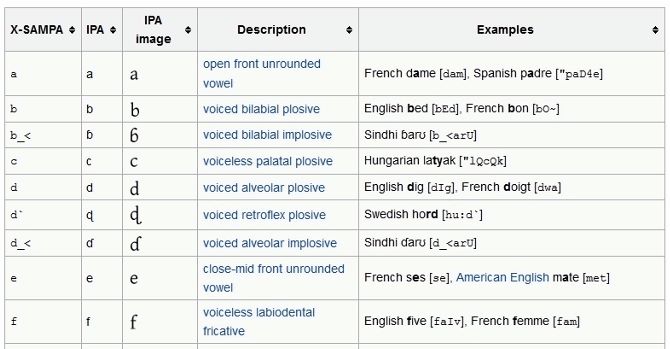

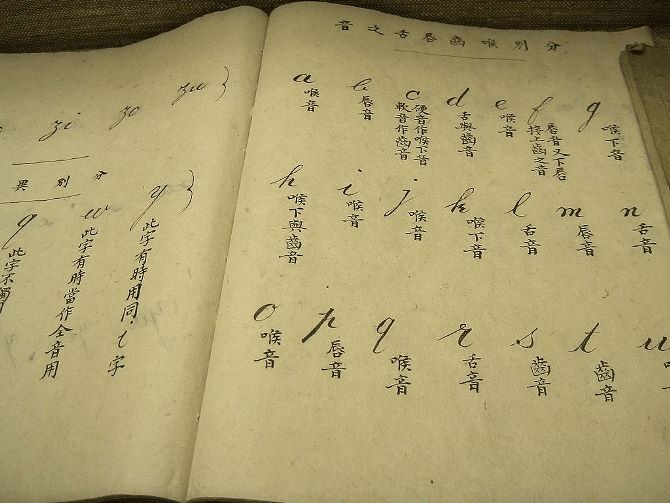

SAMPA and X-SAMPA A third problem with the IPA has actually come about because of the increase of computer usage. While much of the IPA is based on Latin letters, there are also a large number of extra characters and diacritics which cannot be easily typed into a computer. Even then, a specific font is required to display and print them correctly.  Table showing X-SAMPA, IPA, description of sound, and language sound equivalencies This display issue was tackled in the 1980s with the creation of the Speech Assessment Methods Phonetic Alphabet, or SAMPA. Simply put, it is the IPA converted into basic ASCII (the common symbols you can reproduce with a keyboard). It uses the same letters as IPA whenever possible, but replacing them with others when necessary. For example, the schwa (an upside-down lowercase "e" - ə) in IPA, representing a mid central vowel, is replaced with the "at" sign, @, in SAMPA. SAMPA was developed in the European Commission-funded ESPRIT project "Speech Assessment Methods" (SAM), and was initially created just to cover the sounds of English, Spanish, German, French, Italian, Dutch, and Danish. Each set of symbols only matched the language they were made for, similar to the way the IPA was first created. Therefore, a revised set was made, to include all languages in a standardized version. This is known as X-SAMPA. This was all done before Unicode, the system to represent all the characters of all the languages of the world, was supportive of the IPA. Now that Unicode and its full computer version, UTF-8, are so widely used, the need for SAMPA and X-SAMPA has greatly decreased. However, it is still a system that should be recognized alongside IPA for those who may not be able to properly display Unicode. Kirshenbaum SAMPA and X-SAMPA are not the only attempts to make IPA easier to use on computers. In 1992, a group of developers, led by Evan Kirshenbaum, also started creating a system which mapped IPA to ASCII characters. Like SAMPA, they used the existing IPA alphabet when possible, linking each phonetic character to a single keyboard character. Then they would apply extra ASCII characters for IPA diacritics. As a comparison between the three, we can use the Swedish "Sj" sound. It is a voiceless fricative phoneme and represented in IPA by [ɧ]. This is not a character which is available on a keyboard, so in X-SAMPA and Kirshenbaum, it would be written as /x\/ and /x^/, respectively. Note that IPA is normally enclosed in brackets ([]) while SAMPA is surrounded by slashes (//). Phonetic Equivalence  Schoolbook used by the boy emperor Puyi. The page shown is explaining in Chinese how and where in the mouth to pronounce the Latin letters Now, if you are like me, neither IPA nor SAMPA are going to be of much used to when you still do not understand how to match those phonology terms to the way you move your mouth. Most people who are attempting to learn a language do not want to learn a whole other system just so they can properly pronounce "cappuccino". For this reason, many phrasebooks and pronunciation charts depend on "phonetic equivalencies" to describe how a letter is pronounced. What they do is attempt to tell the reader what the sound is like or similar to in their own language and, when there is a difference, approximate the sound using examples. Taking the example of "cappuccino", you could look at an Italian pronunciation chart to see how to say the letter "c". IPA would list it as "[tS]" and "[k]" (it can have two sounds) and SAMPA would list it as "/tʃ/" and "/k/". The sounds could be described as "voiceless postalveolar affricate" and "voiceless velar plosive". That is all fine, if you understand those meanings or the symbols. The average person who has just picked up a phrasebook for their trip to Italy is not likely to. In that case, the phrasebook is more likely to describe the sound (assuming it is an Italian phrasebook for English speakers, since equivalencies are based upon the person's native language) as something like

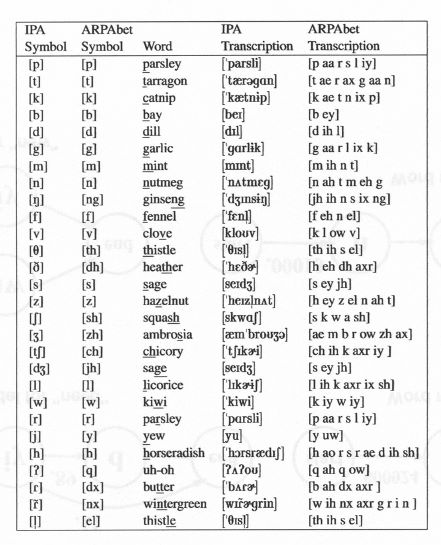

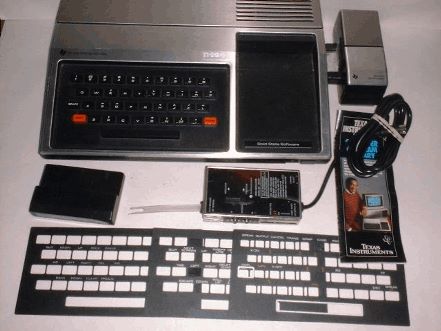

• When followed by "e" or "i", as "ch" in English "cherry"  Table showing both IPA and Arpabet transcriptions for sounds. This method of approximation is not going to be as accurate as IPA or SAMPA, especially since those English words might be spoken differently depending on region and dialect. However, for most people, it is a start, and will give them the confidence to try to pronounce the language. And isn't that the important thing? Some phrasebooks and learning books would also use a phonetic system to show how entire words should be pronounced. “Cappuccino” could be represented by "cap-poo-CHEE-noh" or "kahppootcheenoa", with each syllable being spelled out in English phonetics. Notice how much of a difference there is between the examples; there is no standard method for writing things phonetically. While the IPA methods might scare a learner, a native speaker or IPA user would be laughing at the phonetic equivalencies. Arpabet Getting a person to properly pronounce the sounds of a language is a complicated task. It gets even more difficult to teach a computer how to speak. Believe it or not, there was another phonetic representation system devised to map English language sounds to ASCII, but this one was not based upon IPA.  Old computer with speech synthesizer, designed to approximate human pronunciation As part of the Speech Understanding Project (1971–1976), the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) matched each sound with one or two capital letters. Digits were also added, indicating stress by being placed at the end of the stressed syllabic vowel. Even punctuation marks were included, used similarly to the written language, which helped to show intonation changes, like at the end of sentences and clauses. When home computers became available in the 1980s, Arpabet became the method of programming speech synthesizers for various machines, including the Commodore 64, the Amiga, and the IBM PC. It is still in use today in the CMU Pronouncing Dictionary, a public domain pronouncing dictionary created by Carnegie Mellon University. Lahst Werd Given all the problems involved in representing pronunciation in writing, when you are learning the sounds of a new language, the best advice is to find a native speaker and hope they have the patience to let you practise on them. If that is not possible, you should invest in some kind of audio course or guide.  All of the written methods have their purposes, strengths and weaknesses, and will continue to be used in phrasebooks and course books. Perhaps some newer methods will be created in the future, hopefully one that uses simpler symbols and descriptions than IPA without the wild variations that exist with phonetic equivalences. Then maybe I can finally order that cappuccino! |

| How Do You Say It? - A look at sound notation systems | |||||||||

| Writer: | Erik Zidowecki | ||||||||

| Images: | |||||||||

| |||||||||

All images are Copyright - CC BY-SA (Creative Commons Share Alike) by their respective owners, except for Petey, which is Public Domain (PD) or unless otherwise noted.

comments powered by Disqus