The Tribes of the Tamil-Kannada

|

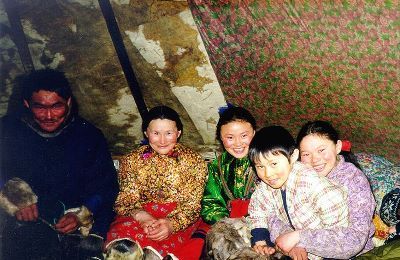

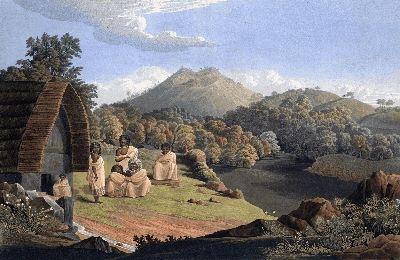

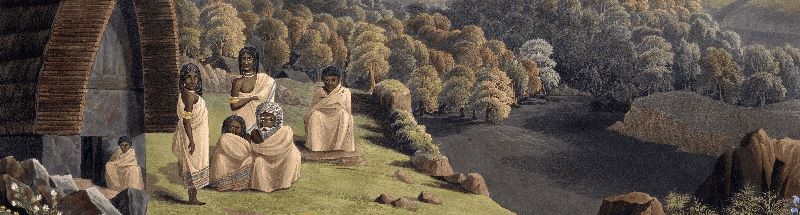

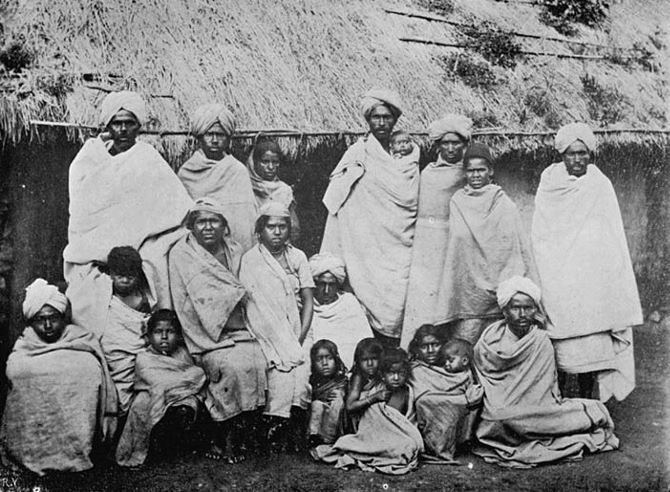

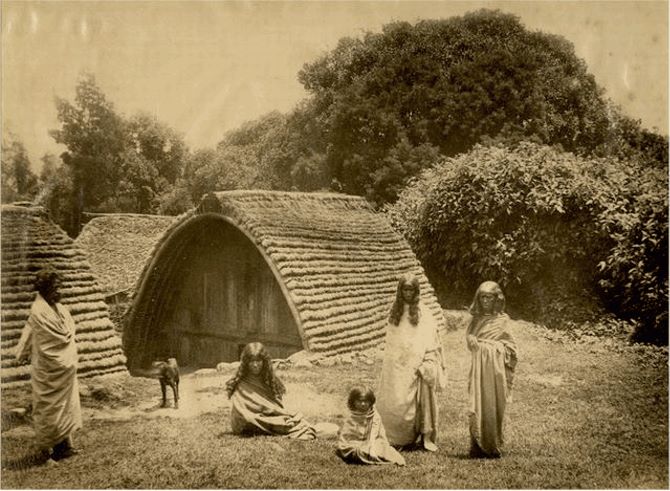

In southern India is an area called the Nilgiri Hills, or the Blue Mountains. It lies in the Tamil Nadu region, at a junction of Karnataka and Kerala and is home to many indigenous tribes which have been there for thousands of years. Now, some of them are in danger of dying out, and with them, their languages. Three of those are Badaga, Kota, and Toda. The major languages of the region belong to the Tamil-Kannada branch, which includes Tamil, Kannada and Malayalam. Those three are recognized among the official languages of India, as well as being officially recognized as classical languages by the Government of India. Our three are not so fortunate, although they are probably as old. Badaga  Map of Nilgiris district, Tamil Nadu, India Badaga is one of the southern Dravidian languages and is spoken by around 400,000 people in the Nilgiri Hills. It was once considered a dialect of Kannada, and while it has many similarities with its Kannada language neighbours, it is now recognized as an independent language. The word Badaga itself refers to both the language and the people that speak it. They are split into almost 440 separate villages, called hattis, and they have inhabited the land for thousands of years, going back at least as far as 8000 BC. As far as it is known, Badaga has not had a writing system for most of its existence. Over the past century, a few different methods for writing Badaga were created, using a mix of the Latin and Kannada alphabets, with the earliest of these dates back to 1890. More recently, Anandhan Raju created a new alphabet, this one based on Tamil, in 2009. and the most recent was published in 2009 by Anandhan Raju. As was common with many indigenous people, the Badagas were visited by missionaries, attempting to convert them. During the Mauryan Empire (322 – 185 BCE), Buddhist monks came to Nilgiris to spread Buddhism among the Badagas, although they probably failed to have much of an impact. However, the various missionary attempts did allow for the languages to be well studied, leading to several English-Bagada dictionaries being published. A Badaga king named Kalaraja was ruling the people in 1116 AD, but he was killed during a war with the Kannada speaking Hoysala empire (1026 - 1343), bringing the Badagas under the rule of King Vishnuvarthana. It later came under the rule of the Vijayanagar empire (1336 - 1646), then the British.  Badaga caste of Nilgiri Hills, from "Castes and Tribes of Southern India" (1909) Now, not all of this information is without some debate. There are some that claim the Badaga people are not actually natives of the region, but rather migrated to there from central and eastern Europe. According to this idea, they arrived in southern India then moved into the Nilgiris Hills when they were under the Vijayanagara Empire, and the people had to adopt the dialect of Kannada. They did not accept the writing system, however, which is why they did not have one when later people found them. This initial group was probably very small, only around 30 people, but a later, larger group migrated as well later. There is no real evidence to confirm this theory, however, while there are clues to validate the idea that they have been there since ancient times. First, according to philology (the study of language in written historical sources), beginning languages didn't have scripts and only develop scripts later on, supporting the idea that the language is very old. Also, before the Badagas converted to Hinduism, they were nature worships, like ancient Greeks and Egyptians, again supporting the idea that they have been around for much longer. Even now, worshipping stones is a central aspect of their lives in the Nilgiris. While their origins might be in question, it doesn't appear their future is. While there is no oppressing force trying to wipe out the language or the people, the Badagas as a people are in decline, and are thus on the endangered list. Kota  Photograph of two Toda men and a woman, taken by an unknown photographer from the Madras School of Arts circa 1871-72 The second language found in the region is Kota. The people of the Kota tribe have a much smaller population than the Badagas, with only around 900 native speakers still living. This number wasn't much larger in the 1800s, with just 1,100 speakers. Although Kota is closely related to neighbouring Toda, it was identified as an independent Dravidian language by Robert Caldwell in the 1870s and probably broke off from the common south Dravidian languages a few thousand years ago. The Kota tribe became isolated, allowing for the language some unique characteristics. Similar to the Badagas, there are a few theories about the Kota people’s origins. It is believed that their ancestors arrived in the region a few centuries ago, when the Badagas were already there. They did not remain isolated forever, as they eventually established a relationship with the Todas people, leading to the trading of buffalo milk, hides, and meat. They also set up trade with local Kurumba and Irula tribes, who were farmers and hunters. This went on for a long time, until the British moved in during the start of the 19th century. Unlike the Badaga and Kota, who adopted Hinduism to varying extents, the Toda people have a religion which mainly centers around the buffalo. After that, missionaries, anthropologists, and linguists, from both India and western countries, spent a huge amount of time studying the tribal groups. One of these was a German missionary, F. Metz, who speculated that, according to some of their traditions, the Kota people came from what is now Karnataka in south west India. The Kotas have for the last 150 years been a small group, no larger than 1,500 individuals spread over seven villages. They have worked in many trades as everything from potters, agriculturalist, and leather workers to carpenters, and black smiths. After the British arrived, they used some of the educational opportunities given to them to improve their socio-economic status, and are thus no longer so dependent on their traditional trades. Unlike the Badaga who adopted Hinduism long ago, the Kota believed in non-anthropomorphic (which means they weren't given human characteristics) male deities and a female deity. Some Hindu deities have been added since the 1940s, and have had Tamil style temples built for them as well as having groups of priests assigned to keep the Kota people in favour with them. Today, most Kota children study in Tamil at schools and are bilingual in both Kota and Tamil, yet the language is still becoming less popular, so it is listed as "critically endangered". Toda  Kota women wearing their traditional dress and ornaments I have already mentioned the third language, Toda, and the people's interaction with the Kota tribe. As of 2001, there was an estimated 1600 native Toda speakers, living on the Nilgiri plateau. They have existed there with the other Kota and Kuruba tribes in a peaceful community until the 18th century, after which they fell under the heavy scrutiny of missionaries and anthropologist, along with the rest. The Toda people probably migrated to the area at about the same time as the Kota, but they also isolated themselves for centuries. The language has a disproportionately high number of syntactic and morphological rules which are not found in other south Dravidian languages. The Toda people not only live rather isolated from other tribes, but even separate themselves from each other, living in settlements of three to seven small thatched houses, built in the shape of half-barrels and spread out on the slopes of the plateau. Toda temples are similarly built in a circular pit while is lined with stones. Unlike the Badaga and Kota, who adopted Hinduism to varying extents, the Toda people have a religion which mainly centers around the buffalo. Sacred places are associated with dairy temples and buffalo herds, and they have traditions and rituals to match them. For example, the Toda religion forbids people from walking across bridges, as rivers must be crossed on foot or by swimming. No shoes may be worn.  Toda people in front of their hut in the Nilgiri Hills Toda legend tells how the goddess Teikirshy and her brother first created the sacred buffalo, then the first Toda man. Similar to the Christian story, the first Toda woman was created from the right rib of the first Toda man. Some Toda pasture land was during the end of 20th century to outsiders and the government, threatening the culture and the buffalo herds. To counteract this, UNSECO has intervened, and the Toda lands are now a part of The Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. The people and language remain critically endangered, however. Conclusion Often, indigenous languages die because they are oppressed by an occupying force and forbidden, or the native speakers start switching to a more dominant language. While these three languages are certainly feeling some pressure from outside forces, it seems they are simple dwindling in population, as tribes are likely to do in the modern age. Even with the efforts of UNESCO, the languages of these people are likely to be completely gone within the next few decades. |

| Languages in Peril - The Tribes of the Tamil-Kannada | ||||||||||||||||

| Writer: | Lucille Martin | |||||||||||||||

| Images: | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| Sources: | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

All images are Copyright - CC BY-SA (Creative Commons Share Alike) by their respective owners, except for Petey, which is Public Domain (PD) or unless otherwise noted.

|

Searching for language resources? Find entertaining and educational books for learning a language at Scriveremo Publishing. Just click the link below to find learning books for more than 30 languages!

| |

comments powered by Disqus