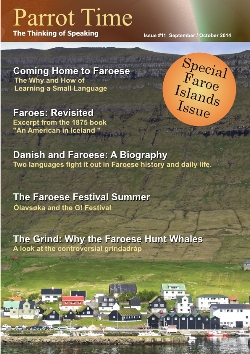

The Grind: Why the Faroese Hunt Whales

|

If We Lose Our Foods,

We Lose Who We Are by Elin Brimheim Heinesen

Compiled with permission from her blog http://heinesen.info/wp/ I was born in the late 50′s in the Faroe Islands. At that time we pretty much had a subsistence way of life in this remote place on earth with a hostile climate and an environment that humans could never hope to survive in without eating animals. In winter, our region is stormy and dark for months on end, and the summer is very short. There are no trees except some imported trees in sheltered areas inside the villages and just a few edible plants. And yet, somehow we, the Faroese people, have survived here for more than a thousand years, relying on an intimate knowledge and understanding of our environment for our survival, constantly walking a tightrope between life and death. In my childhood we still harvested most of our own food, integrating healthy, wild edibles into our diet. Most of our food supply was right outside our front door, and we used time-tested methods for living off the land and the sea. Our people were unencumbered, only depending on nature’s resources and the skill in our hands. Sudden food cost increases or empty grocery shelves caused by turmoil on the international market were not our biggest concerns. The only uncertainties were the whims of nature. I remember the foods of my childhood. We ate mostly fish, some sheep meat and quite a lot of whale meat and blubber, served with homegrown potatoes. And afterwards we would have porridge made from homegrown rhubarbs, for instance. Our storage of dry and salted food and our new freezer were filled with fish, sheep meat and whale meat and blubber, my family had provided directly from natures larder. Our dairy products were from local farmers. But the grains, flours and sugar we used for baking bread and cakes were imported. And we only ate vegetables and fruits, if we could afford it. They were very expensive, because they came from far away, so they were luxury foods, we could not have everyday. But things changed. Our fishing became industrialized. We got money on our hands. And suddenly we were able to import exotic foods from countries far away, like oranges and bananas. When I was a teenager in the 70′s, we probably already ate fifty-fifty, half traditional Faroese food, half regular European food. Today the division is more like eighty-twenty, at least for people living in the bigger towns, while people in smaller and less affluent villages still try to reduce food costs by holding on to the old traditional diet.  Sheep grazing on a hill in the Faroe Islands. They are part of the Faroese standard diet. But it’s very doubtful whether the modern foods replacing the traditional foods, are any better or healthier. The opposite is more likely. The closer people live to towns and the more access they have to stores and cash-paying jobs, the more likely they are to have westernized their eating. And with westernization comes processed foods and cheap carbohydrates—soda, cookies, chips, pizza, fries and the like. The young and urbanized are increasingly into fast food. So much so that type 2 diabetes, obesity, and other diseases of Western civilization are becoming causes for great concern in our country too. Well, it seems that there are no essential foods—only essential nutrients. And humans can get those nutrients from diverse sources. One might, for instance, imagine gross vitamin deficiencies arising from a diet very scarce on fresh fruits and vegetables. People in southern climes derive much of their Vitamin A from colorful plant foods, constructing it from pigmented plant precursors called carotenoids (as in carrots). But vitamin A, which is oil soluble, is also plentiful in the oils of cold-water fishes and sea mammals, as well as in the animals’ livers, where fat is processed. These dietary staples also provide vitamin D, another oil-soluble vitamin needed for bones. Those living in temperate and tropical climates, on the other hand, usually make vitamin D indirectly by exposing skin to strong sun—hardly an option in the long and dark winters in the north. If you have some fresh meat in your diet every day and don’t overcook it, there will be enough vitamin C from that source alone to prevent scurvy. Traditional Faroese practices like freezing or drying meat and fish and frequently eating them raw, conserve vitamin C, which is easily cooked off and lost in food processing, so eating dry fish, sheep or whale meat and blubber is as good as drinking orange juice. Fats have been demonized in modern western cultures. But all fats are not created equal. Wild animals and / or animals that range freely and eat what nature intended have fat that is far more healthful. Less of their fat is saturated, and more of it is in the monounsaturated form (like olive oil). What’s more, cold-water fishes and sea mammals are particularly rich in polyunsaturated fats called n-3 fatty acids or omega-3 fatty acids. These fats appear to benefit the heart and vascular system. But the polyunsaturated fats in most Europeans and Americans’ diets are the omega-6 fatty acids supplied by vegetable oils. By contrast, whale blubber consists of 70 percent monounsaturated fat and close to 30 percent omega-3s. A young woman of childbearing age may choose not to eat certain foods that concentrate contaminants. As individuals, we do have options. And eating our fish, our sheep and our whale meat and blubber might still be a much better option than pulling something processed that’s full of additives off a store shelf.  Tvøst og spik - a traditional dish of the islands, consisting of pilot whale meat (black), blubber (middle), dried fish (left), and potatoes How often do you hear someone living in an industrial society speak familiarly about “our” food animals? How often do people talk of “our pigs” and “our beef?” Most people in the modern world are taught to think in boxes and have lost that sense of kinship with food sources. But in the Faroese hunting and farming village culture the connectivity between humans, animals, plants, the land we live on, and the air we share has not been lost––not yet, at least. It is still ingrained in most Faroese people from birth. Many of our young people and people in bigger towns are quite influenced by western urbanized culture and food habits. They are slowly getting alienated to our old traditions. However, it is still not possible, really, to separate the way many of us still get our food from the way we live in this society as a whole. How we get our traditional food is intrinsic to our culture. It’s how we pass on our values and knowledge to the young. When you go out with your father, mother, aunts and uncles to fish in the sea, to heard the sheep, handle the wool, to gather plants, to hunt birds and other animals or catch whales, you learn to smell the air, watch the wind, understand the way the currents move and know the land. You get to know where to pick which plants and what animals to take. This way of life has been an integrated part of our culture for so long, and it still is to a degree, especially in the smaller villages, where people share their food with the community. They show respect to their elders and the weak in the society by offering them part of the catch. They give thanks to the animals that gave up their life for their sustenance. They get all the physical activity of harvesting their own food, all the social activity of sharing and preparing it, and all the spiritual aspects as well. You certainly don’t get all that when you buy prepackaged food from a store. That is why some of us here in the Faroe Islands are working hard to protect what is left of our old way of life, so that our people can continue to live and work in our remote villages, as independently as possible from polluting transport systems and a fraud-full modern economic infrastructure. Because if we don’t take care of our food, it won’t be there for us in the future. And if we lose our foods, we lose who we are. PT Elin Brimheim Heinesen is a Faroese journalist and freelance consultant. For more on this subject and her complete blog visit http://heinesen.info/wp/.

|

| The Grind: Why the Faroese Hunt Whales | |||||||

| Writer: | Elin Brimheim Heinesen, Morten Ejner Hønge, Miranda Metheny | ||||||

| Images: | |||||||

| |||||||

| Sources: | |||||||

| |||||||

| Miranda was the editor for these articles and wrote the introductory paragraphs | |||||||

Miranda Metheny retains all copyright control over her images. They are used in Parrot Time with her expressed permission.

All images are Copyright - CC BY-SA (Creative Commons Share Alike) by their respective owners, except for Petey, which is Public Domain (PD) or unless otherwise noted.

comments powered by Disqus