Revisted

The Faroe Islands

|

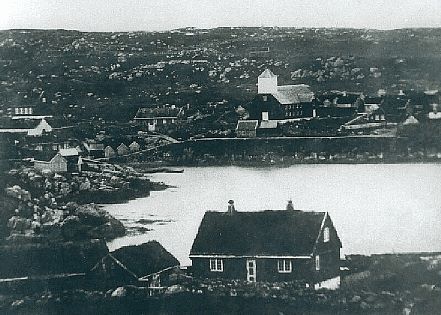

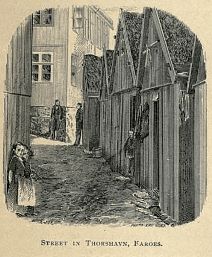

Editor's note: The is a reprint of a chapter from "An American in Iceland", written by Samuel Kneeland and published in 1875. The author visted Iceland, the Faroe Islands, the Orkney Islands, and the Shetland Islands in 1874.  Tórshavn, the capital of Faroe Islands, in the morning of 11 August 2003 Our pilot left us in about two hours, to pursue our unerring course, thanks to good seamanship and the power of steam, through fog and wind and storm, to the Faroes, distant one hundred and eighty-five miles in a north-westerly direction. Darkness was not added to the other dangers, a sort of semi-twilight, in spite of the misty clouds, lasting all night. The sea was very rough, and most of us paid tribute to Neptune, who moreover asserted his victory over me by making me thoroughly uncomfortable; I was very glad that no importunate newspapers were looking to me for a hurried account of the strange things we saw. In the afternoon we came in sight of the southern island of the group, passing some fine scenery which the occasionally lifting fog enabled us to get glimpses of. As usual, we got lost in the fog, and had to feel our way very slowly among these dangerous rocks, knowing that the strong currents must have taken us somewhat out of our course. We finally were cheered by the sight of the greater Diman, a melancholy-looking rock, about a mile long by half a mile wide, one of the most inaccessible of the group; even this rocky monster had a pleasant look, as it told us just where we were. The shore is so steep that no boat can be kept there, and the wretched inhabitants are almost shut off from their kind; the clergyman, who visits them once or twice a year, has to be pulled up by ropes from the cliffs. It is a great place for the breeding of sea-birds, whose young and eggs supply a large part of the food consumed there. The mountains were, at least, half a mile high, and the cliffs with their base in the sea and their summits in the clouds, with precipitous sides rent by deep and narrow chasms, tenanted by innumerable sea birds, whose harsh voices were louder than those of the wind and waves, were singularly grand and picturesquely dreary.  The Løgting, parliament of the Faroe Islands, 1864 The Faroe Islands, as far as coast scenery and people are concerned, are a sort of Iceland in miniature. Settled by the same fierce Northmen who were driven from Norway by Harald, the Fair-haired, their greater distance from Great Britain, and their consequently more isolated situation, in connection with the difficulty and danger of reaching them in the foggy and stormy northern ocean, have given them a peculiar character, very different from the poetic and literary Icelanders of the olden time. I say of the olden time, as at the present day, poetry, literature, and even ordinary energy have ceased to be characteristic of the down-trodden, too much governed, Iceland. The name is derived from faer, a sheep. The group rises from the ocean, between 61° and 62° N. lat, with high perpendicular cliffs of the wildest character, indented by deep gulfs or bays, and fashioned into the most fantastic forms, tenanted by innumerable birds. About twenty out of thirty-five small islands are inhabited, the rest being naked rocks, inaccessible, except to sea-birds, and daring bird and egg hunters. The extent of open sea in all directions, three hundred and twenty miles to Iceland and over four hundred to Norway, exposes them always to the fury of the waves, which dash, even in calm weather, with violence against the rocks; the water is very deep close to the shore, and the currents are very strong and dangerous in the fogs which there abound. The climate is not severe, being tempered by the ocean; grass grows at an elevation of 2000 feet, though the mountain tops, some 900 feet higher, are perfectly barren; the absence of trees here, as well as in Iceland, is due to the high winds and the salt mist, and not to excess of cold. Barley, the only grain which will grow in Faroe, ripens at elevations varying from 80 to 400 feet, according to northern or southern exposure. The Faroese, though belonging to the same stock as the Icelanders, were never, like them, a literary people, probably, because the population was a very fluctuating one with decided piratical tendencies, most of the early colonists having come from the Loffoden Islands, off the coast of Norway. Though nominally subject to Norway, they were practically independent, refusing to pay tribute, and apparently for a long time forgotten by the mother country, their fierce manners being rendered more peaceful by Catholic Christianity.  From the book of this article, circa 1875 From their exposed situation they were frequently plundered by pirates, English, French, and Turkish, though afterwards protected by Denmark, when this country was united to Norway. During our revolutionary war, much of our colonial produce found its way there, whence it was smuggled into Scotland. Being wholly unprotected, during the wars of the northern nations, they suffered great privations from the interruption of trade, to such an extent that England, in 1809 to 1811, allowed them to trade with some of her ports, as stranger-friends, too feeble to act as enemies and powerless as friends. This will account for the extent to which the English language is spoken by the old traders at Tórshavn. In 1814, the peace restored them to Denmark, which has monopolized the small trade ever since, with the usual oppression of monopolies. Their agricultural products are small, as, from the rocky character of the soil, most of the cultivation must be done with the hoe instead of the plough. Beside the pursuit of the cod and herring fisheries, the taking of seals and whales is an important industry. When a school of dolphins is in sight, the joyful news is communicated by signal fires, and the boats, to the number of several hundred, soon form a huge semicircle around the prey, driving them into shallow water with shouts and blows, where they are quickly killed by the excited crowd. The flesh is eaten fresh and dried, and the blubber, is converted into train-oil for food and various uses. Almost all kinds of sea-fowl, the gulls and cormorants excepted, are eaten, fresh, salted, or dried, as, also, are their eggs. They raise many cattle, ponies, and sheep, for which the fields are well calculated; from the latter, as in Iceland, the wool is pulled instead of being shorn, the portions ready to fall being taken at each time. The people are healthy and long lived, but do not increase rapidly. Though nominally subject to Norway, they were practically independent, refusing to pay tribute, and apparently for a long time forgotten by the mother country. It was 9pm when we reached the capital, Tórshavn, on the principal island, Stromoe, which contains about one hundred and forty-three square miles, being on an average about twenty-six miles long and nearly six miles wide. These islands were known to the Norwegian rovers before the settlement of Iceland, this last having been discovered by the former toward the end of the ninth century; they were not chosen for fixed habitations till the wars of Harald drove the chiefs and their followers from Norway to the northern islands. They are now the property of Denmark, and at Tórshavn we found the ships of his Danish majesty, just arrived from Copenhagen on their way to attend the Iceland millennial celebration; they had put in for the double purpose of taking on coal and of visiting this distant dependency. We saw the flag of Denmark, a white cross on a scarlet ground, floating from the masts of two men-of-war, from several smaller vessels in the harbor, and from numerous points on shore, which we at first took for grassy hillocks, but afterward discovered to be roofs of turf-covered houses. We had left British waters, and were anchored in the seas once ploughed by the Scandinavian sea-kings. We here first came into contact with a pure Norse people, and first saw the form of house almost universal in Iceland, with low walls and roofs overgrown with grass-bearing turf, hardly distinguishable from the ground about them except for the wreaths of smoke and the flags. It being quite light we went ashore soon after coming to anchor.  Two girls in Faroese costume The town is situated on the rocky hills surrounding two exposed bays separated by a peninsula; the houses are placed in utter confusion, wherever intervals between the black rocks or any level surface will permit. This, while it adds in one sense to the picturesqueness as seen from the sea, makes getting about in any definite direction very difficult. There can hardly be said to be any streets, but steep, irregular, narrow, stone-paved lanes, sometimes in front and sometimes in the rear of the houses, and often admitting only persons going in single file; the pavements were slippery from fish-skin and refuse, and the sides redolent of fish and the slops of the houses; it reminded me of some of the streets in New York near the wharves and markets. The houses were generally small and miserable, made of wood, tarred to preserve them from dampness, with sod-covered roofs; the fronts and projecting corners were adorned by strings of fish in every stage of decomposition, the attempt at drying them in such a moist air being, according to my nasal organs, often a decided failure. The odors of fish and oil predominated everywhere, and the interior of the houses betokened discomfort, dampness, closeness, and want of cleanliness, which must be a fruitful source of disease and premature death, especially in children. It was a dismal day, and it was to me impossible to associate any idea of home with such dwellings. In some of the better houses, of two or more stories, lace curtains and flowers gave a cheerful look to the windows, and evidences of woman's taste. Though night by the clock, it was light, and the shops were open and crowded. We went into one pestiferous place, through a dark, ill-paved, and winding alley, where we found men drinking in one corner, and in another some women buying gewgaws for the morrow's celebration with all the eagerness, chatter, and apparent satisfaction of a shopper on Broadway. The odor was overpowering from reeking garments, wet shoes, unclean bodies, and the organic and inorganic stock upon the shelves; any thing could be procured here from a needle to an iron chain, from a bit of candy to a pound of snuff, from a keg of fish to a bottle of brandy. The Norse characteristics of the people were evident at a glance; the abundant light hair and beard, blue eyes, ruddy complexion, tall stature, and stalwart form, revealed the old Viking race. The physical appearance and dress of the people were much like those of the Norwegians, and their habits those of fishing communities in high latitudes; a very little agriculture, a little grazing, and a great deal of fishing, are their occupations. They were very respectful, raising their Phrygian caps as we passed, and bidding us good-evening. The men wore breeches of woollen material, of their own manufacture, buttoned below the knee, and upper garments like northern fishermen; long woollen stockings and seal-skin shoes, kept from the wet pavement by clattering wooden clogs, completed their attire. I saw nothing peculiar about the female costume; the inevitable shawl around the shoulders, and a head-dress consisting of a black-silk handkerchief tied behind with a point toward the forehead, were not at all becoming. Just before our arrival the king had made his official entry, and the harbor was still gay with flags and rushing boats, and the streets were spanned with arches and strewed with flowers. The people in gala dress were quietly watching the processions, and the petty officials were strutting around with all the pomp and feathers of one of our militia trainings. Such an important event as the landing of a king, for the first time since their occupation by Denmark, was deemed worthy of a formal address by the mayor, but so overpowered was he by the grandeur of the occasion, that his loyal heart could not bear the emotion, and he fell dead at the very feet of the king. This, of course, gave a tone of sadness to what otherwise would have been universal rejoicing. |

| Revisited - The Faroe Islands | |||||||

| Writer: | Samuel Kneeland | ||||||

| Images: | |||||||

| |||||||

| Sources: | |||||||

| |||||||

Miranda Metheny retains all copyright control over her images. They are used in Parrot Time with her expressed permission.

All images are Copyright - CC BY-SA (Creative Commons Share Alike) by their respective owners, except for Petey, which is Public Domain (PD) or unless otherwise noted.

comments powered by Disqus