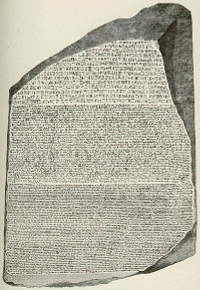

The Rosetta Stone

Triple Cypher

|

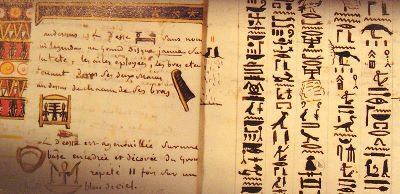

Translating the Stone The easiest part of the Stone to translate was the Greek, for while knowledge of the Greek language and alphabet were limited among certain scholars, the Western world had become acquainted with Greek centuries ago, during the Renaissance. In 1802, the Reverend Stephen Weston completed his translation of the Greek text. While this didn't garner much attention, it would provide the basic text to build the other translations upon.  The Rosetta Stone In 1802, French scholar Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy and Swedish diplomat Johan David Åkerblad both set about to translate the Demotic portion of the Stone. De Sacy was able to detect the proper names of "Ptolemy" and "Alexander" in the text and used those as a starting point for matching up sounds and symbols. Åkerblad, however, approached the work using his knowledge of the Coptic language. He noticed some similarities between the Demotic and Coptic inscriptions, and by comparing these, he was able to decode the words "love," "temple" and "Greek." He attempted to use those as a basic outline for the rest of the translation. He managed to find the correct sound values for 14 of the 29 signs, but he wrongly believed the demotic hieroglyphs to be entirely alphabetic. Both de Sacy's and Åkerblad work, however, provided vital clues, and an English polymath (a person whose expertise covers a significant number of subjects) Thomas Young was able to completely translate the Demotic text in 1814. He then started work on deciphering the hieroglyphics.  Thomas Young When hieroglyphics had been first discovered, one of the earliest attempt at translating them came from a fifth-century scholar named Horapollo. He set up a translation system based upon hieroglyphics' relation to Egyptian allegories. This hypothesis led to 15 centuries of scholars dedicating themselves to using this translation system as they tried to decode the ancient writings. However, they all failed, because the basic premise, it would turn out, was false. Some of the later scholars that were working on it were the German Jesuit Anthonasius Kircher, the English bishop William Warburton and the French scholar Nicolas Freret.  Hieroglypics showing a cartouche Young made an important breakthrough in the same year that he completed the Demotic when he discovered the meaning of a cartouche. A cartouche is an oval-shaped loop that around a series of hieroglyphic characters, and he realized that these cartouches were only drawn around proper names. That enabled him to identify the name of Ptolemy. Figuring that a name sounds similar across languages, Young parsed out a few sounds in the hieroglyphic alphabet using Ptolemy's name and the name of his queen, Berenika. However, Young was also relying on Horapollo's premise that pictures corresponded to symbols, so he couldn't quite figure out how phonetics fit in. Young gave up the translation but published his preliminary results in 1818.  Jean François Champollion A former student of de Sacy named Jean François Champollion had also been studying the hieroglyphics of the Rosetta Stone since he was 18, in 1808. He picked up where Young left off, but didn't make much headway for a few more years. Then, in 1822, he was able to examine some other ancient cartouches. One contained four characters, with the last two being the same. After identifying the duplicated letter as being "s", he looked at the first character, and guessed it to represent the sun. Here, Champollion made a leap using his knowledge of Coptic, in which the word for sun is "ra". This gave him the name of "ra-ss", and he only knew of one name that would fit: Ramses, another Egyptian pharaoh.  Part of Champollion's work on decyphering the hieroglyphics This connection between hieroglyphics and Coptic showed to Champollion that hieroglyphics wasn't based on symbols or allegories at all. They were phonetic, so the characters represented sounds. He was then able to correct and enlarge Young's list of phonetic hieroglyphs, and finally, using this knowledge and comparing to the other translations of the Demotic and Greek, translate the rest of the Stone. That same year, his achievement was announced in a letter he wrote to the French Royal Academy of Inscriptions, in which he outlined the basic concepts of hieroglyphic script: Coptic was the final stage of the ancient language, the hieroglyphs were both ideograms and phonograms, and the glyphs in cartouches were phonetic transcriptions of pharaohs' names. The hieroglyphics code had been broken. Politics Both France and Britain competed on many levels over the Rosetta Stone. After the initial struggle of ownership, their was also a disagreement about who did the "real work" of translating. The British claimed that Young completed the Demotic and made the breakthrough on the hieroglyphics by figuring out the cartouches. The French claimed that Champollion was the true translator, for it was his insight using Coptic that led to the translation.

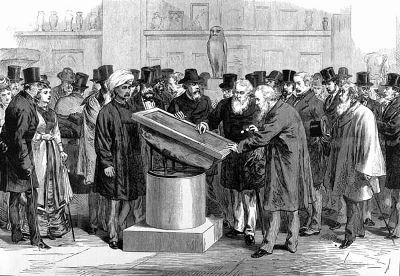

Experts inspecting the Rosetta Stone during the International Congress of Orientalists of 1874 Moreover, when Champollion published his translation in 1822, Young and others praised his work, but Young published his own work on it in 1823, to ensure his contribution to Champollion was recognized, even pointing out that many of his findings had been sent to Paris in 1816. Young had indeed found the sound values of six of the glyphs, but had not been able to determine the grammar of the languages. Champollion was unwilling to share the credit, however, further dividing the countries. The two countries remain competitive to this day on who should get credit and who should own the Stone. While the Rosetta Stone was being displayed in Paris in 1972, in celebration of 150 years since Champollion published his findings, rumors flew that Parisians were plotting to secretly steal the Stone. There was even disagreement over the portraits of Young and Champollion that were displayed alongside the Stone, with them being of unequal sizes and thus glorifying one scholar over the other.

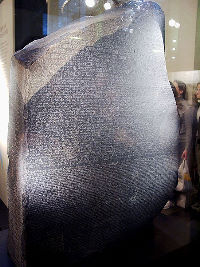

The Rosetta Stone on display The Egyptian government has also been involved with its own claims. In 1999, Egypt made it well known that they would not be celebrating the bicentennial of the finding of the Stone because it was in the hands of the British. They had wanted Western countries to give back Pharaonic period masterpieces, including the Rosetta Stone, in 1996, but UNESCO agreements grant the right to recover items only on those stolen after 1971. Still, in 2003, Egypt again requested the return of the Rosetta Stone. The British Museum sent them a replica in 2005, but refused to give up the Stone. The issue of ownership is very tricky. While technically the Rosetta Stone and all the relics captured by the British from the defeat at Alexandria were legally obtained, and their release granted by representatives of the national government which owned them, that is not the same state of Egypt that exists today. The French could also give possible claim to the Stone as spoils of war. Also, the Rosetta Stone is not like other artifacts found in the exchange. It is not a work of art, or religious icon, and its value arose from the potential information it could yield as a key in the decipherment of hieroglyphs. Therefore, while it a piece of Egyptian heritage, its importance was only fulfilled by the work of the Europeans, both French and British, who translated it. Without that, it was only one of thousands of stones with writing on it. For this reason, it has been seen by some as a piece of "world heritage", and therefore it shouldn't matter where it is displayed. An exact copy also exists in the Egyptian Museum of Cairo, but the politics of who has the original is likely to continue for a very long time. Conclusion The importance of the Rosetta Stone in its aid to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphics can not be overstated. It unlocked the unknown history of so much of the ancient Egyptian culture. So much has since been learned about their history, ways of life, beliefs, and technological advances. It has also aided in solving the mysteries of the pyramids and other ancient events. We still don't know how far its importance will stretch, as Egyptian artifacts, in the form of pharaohs' tombs, are still being discovered. Ironically, while the Stone was originally made to bolster a weak king, its existence opened up the history of all the kings and civilizations that had been lost with the knowledge of the hieroglyphics. |

| Triple Cypher - Rosetta Stone | ||||||||||||||||||

| Writer: | Lucille Martin | |||||||||||||||||

| Images: | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

All images are Copyright - CC BY-SA (Creative Commons Share Alike) by their respective owners, except for Petey, which is Public Domain (PD) or unless otherwise noted.

comments powered by Disqus