The Chibchan Family

|

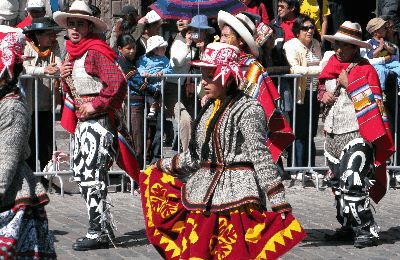

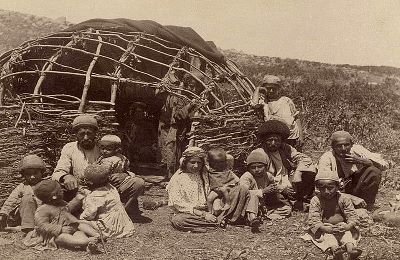

Among the countries of South America, there was once a tribe of indians called the Chibchas. The lived in the high valleys surrounding the modern cities of Bogotá and Tunja in Colombia, having a population of over five hundred thousand. There they thrived until the Spanish arrived and started colonizing the region in the 1530s. It didn't take long for the political structure of the natives to be crushed. The Spanish language began to take hold, but it took it another two centuries before the Chibcha language was completely erased and the natives merged with the colonies. The Chibchan language branch is named for this extinct language, and contains many languages of the area. Many of them still survive, but almost as many are also extinct. The remaining ones are endangered, some severely so. Pech The Pech language, also known as Paya or Seco, belongs to the indigenous Pech people of northeastern Honduras. While they once roamed much of the region, colonization has largely reduced them to living on a few reservations, with the main ones being Vallecito, Marañones and El Carbón. There are a number of much smaller Pech settlements scattered around northern Olancho. It is unknown exactly where the Pech people originated. They may have come from North America over 7000 years ago, but linguistic studies suggest they are descendants of South American tribes. Their language shares many common roots with the people of the south, like the Kuana indians of Panama. The tribes inhabited almost the entire region from the lagoon of Caratasca to the border of Nicaragua. They were a semi nomadic people of hunters, fishermen, and farmers. Before the Spanish colonization, there were thousands of Pech inhabiting the 26,000 square kilometers of land. They were not alone, however, and fought frequently with the neighboring Miskito tribes. Part of the eastern coast of Honduras and Nicaragua eventually became known as the "Mosquito Coast" after these people. During Christopher Columbus's third trip to the New World in 1498, he encountered the Pech and named them Taia. When colonization began, their population was drastically reduced by European diseases as well as continual attacks by the Miskito tribes. By the 19th century, the number of Pech left was less than 1600. However, colonization did not come easily to this region, known as La Moskitia. Both the Pech and Miskito people were strong fighters, and the terrain of the area was difficult for the Spanish to navigate. Believing the best way to control the indigenous people would be through introducing religion and converting them, several expeditions of missionaries were sent, with the first arriving there in 1607, then another in 1609. These were burned by another tribe of indians, the Tawahka.  Children in the fort town, Trujillo, Honduras. A third expedition was sent in 1611, this time with twenty-five armed soldiers to defend against more attacks. Not only did another Tawahka attack fail, but the soldiers captured one of their chiefs and nailed him to a tree. The Tawahkas responded by attacking the fortified village in January of 1612, taking them by surprise during the night, and killing all the soldiers and religious leaders. That kept the missionaries away for ten years, but they returned in 1622, this time establishing a fort town, Trujillo. After traveling a few days into the land, they found a Pech village on the Xarúa river. Unfortunately for the Pech, the missionaries found them to be more open to their evangelism, and in less than a year, half a dozen villages with over 700 members had been converted. Pleased with the results, the missionaries continued to impose their religion on more tribes, converting almost 6000 members of the Guaba and Jicaque indians. They encountered the Tawahkas again in 1623, and when they decided to convert them as well, the head missionaries, Fathers Franciscans and Martinez, were killed. That put an end to any more religious based excursions for many years. Violence came to the Pech when the Spanish invaded their territory in the Aguan valley in 1661 and the Pech attacked them. Captain Bartolome de Escoto counter-attacked, and in the process captured hundreds of the people and made slaves of them. After that, the missionaries were able to really take over the Mosquito Coast, and by 1690 they had founded several villages with a population of 6000 Europeans.  This lasted for around sixty years, during which time non-Spanish settlers arrived from England, France, and the Netherlands. Pirates, called buccaneers, moved into the Mosquito Coast and began attacking the Spanish ships. These buccaneers made alliances with the conquered Miskitos, providing them with guns to fight the Spanish, which they did. By the late 1800s, the Miskitos became the dominant tribe among the others and started invading them. The Pech had no choice but to flee, and so they traveled inland, but their population still suffered heavily. For many years, the entire region was engaged in a power struggle, with the Pech caught in the middle. While most of the missionaries still worked to rule the native people, the nineteenth century brought to the land Spanish missionary Father Manuel de Jesus Subirana, and he dedicated his life to helping the indigenous tribes. He helped the Pech who now lived in Santa Maria del Carbon to obtain titles for their land in 1862. He started petitioning for titles and rights for the Pech of Culmi, and those were obtained 1898. However, ownership for the natives was a rare thing, and they were normally simply pushed off the land they had by Latino ranchers. The Tawahkas responded by attacking the fortified village in January of 1612, taking them by surprise during the night, and killing all the soldiers and religious leaders. Because of this oppression, most of the Pech have abandoned their native language, learning Spanish instead and adopting Latino culture to avoid further discrimination. They have intermarried, further diluting their culture and traditions. Now, both the Pech people and language are on the edge of extinction. Estimates from 1993 are that there were only 990 speakers remaining, with less than 20 of those being "racially pure" and speaking the Pech language fluently. Rama In the South American country of Nicaragua are the remaining members of the Rama Indians. They live mainly on the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua and on the Rama Cay island (a small island in the lagoon of Bluefields). Their native language is Rama, which is one of the Chibchan languages, and with less than 20 people still speaking it, it is critically endangered. The Rama people are one of the indigenous groups of Nicaragua, but it is unknown how long they lived there. The first use of the name Rama doesn't appear in early colonial records until as late as the eighteenth century. Records of the people themselves date much further back. They used to live in small scattered settlements, using the tropical forest for protection from intruders. While the Rama are distantly related to their northern neighbors, the Miskito and Sumo peoples, various linguistic studies put the Rama in the Chibchan language group. This means they are more closely related to the Pech Indians of Honduras, the Guatuso and Talamanca Indians of Costa Rica and the Kuna and Waimi Indians of Panama. As is part of the tragic history of many indigenous groups, much of their population was wiped out when colonizers from Europe arrived, bringing with them many diseases that the natives had no immunities to. A Moravian mission was established on the island in 1857. When the Miskito tribes started attacking Spanish colonized areas and the still independent tribes to fill the demands of a growing slave trade in the late seventeenth century, the Rama found themselves under threat again. While the population decreased, the language also declined. Not only were their fewer people to speak it, but an English Creole began to emerge from Rama and English from years of contact with English pirates, Moravian missionaries, and black Creoles living in the area.  Collection of houses on Rama Cay, Nicaragua This creole was very different from the one that developed in Bluefields from the tribes there. Linguists Barbara Assadi and John Holm found distinct variations of pronunciation, vocabulary, and morphosyntax when compared to the Bluefields Creole. There are some elements of a German accent mixed in, probably influenced by the Moravian missionaries who were native Germans but preached in English. Rama Cay Creole, as it is known now, is also a seriously endangered language. The Rama Cay community is still active today. It has a Moravian church, a community center, an elementary school and a health clinic, as well as several dozen houses. They are hunters, fishermen and farmers, growing mainly bananas and white cacao. A study in 1988 found 58 people who knew the language, with 36 of them being fluent speakers. Most were over the age of 25. There is an attempt to revive the language, with it now being taught in primary school on Rama Cay, but most children are not learning it. Boruca Another endangered Chibchan language is that of the Boruca people of Costa Rica. It has around 30 non-fluent speakers left, with only six elderly natives who speak it fluently. The younger people are not leaning the language beyond basic ability to understand it when spoken, adopting the local language of Spanish as their own. Because of this oppression, most of the Pech have abandoned their native language, learning Spanish instead and adopting Latino culture to avoid further discrimination. The Boruca tribe has about 2.5 thousand members, with the majority of them living on a reservation in the Puntarenas Province of southwestern Costa Rica. Their ancestors were once the chiefs that ruled most the Costa Rica's Pacific coast. The modern Boruca people are known for their art, including their distinctive wood masks being very popular with tourists. These masks are also important in the Borucas' annual Danza de los Diablitos (The Dance of the Little Devils) celebration, which depicts the resistance of the "Diablito" (the Boruca people) against the Spanish conquerors, eventually beating them. It is symbolic, not literal, because the Spanish did conquer them. The symbolism is that their spirit was never broken. The tribe is composed not only of ancestors of the pre-Spanish colonization group but also a mix of people from local tribes, like the Coto, Quepos and Abubaes. The Boruca people and other tribes of Costa Rica were fortunate to avoid being forced into slavery, mainly because there were so few of them, after the Spanish took over, to make it worth the effort. The settlers of Costa Rica had to work on their own land, and this also prevented the establishment of large haciendas (properties). Because of this, Spain largely let Costa Rica develop on its own, and this was good for the tribes because it kept them mostly free from oppression for many years.  Faces of the Boruca people Like the indigenous population, the Boruca language managed to survive and was still "healthy" until the 20th century. Part of this may be because the community became bilingual, using both Boruca and Spanish, rather than directly competing. Despite their claims of fighting against the Spanish invaders, neighboring tribes claim that the Boruca were actually very quick to side with the Spanish invaders, hoping to receive better treatment than those that opposed them. For this reason, they are sometimes called vividores, meaning "opportunists". That may be another reason they sustained so little damage to their heritage for so long. When primary education became more generalized at the start of the 20th century, the schools started forbidding students to use their native language. They were to only use Spanish, and if they were caught disobeying, they were beaten. As a result, the children stopped using Boruca for anything outside of their homes. Soon, the language was no longer being passed on, and the number of speakers dramatically declined. Many Boruca words and phrases can be heard mixed into Spanish conversations, but it is rarely spoken as its own language anymore. In recent years there has been some attempts at reversing this decline. The language is taught as a second language in some local primary schools, but the spirit of the Boruca people has been broken. They are ashamed that their language is now considered so unimportant, and they feel it no longer has a place in the modern world. It seems the Spanish finally did conquer them completely. |

| Languages in Peril - The Chibchan Family | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Writer: | Lucille Martin | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Images: | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

All images are Copyright - CC BY-SA (Creative Commons Share Alike) by their respective owners, except for Petey, which is Public Domain (PD) or unless otherwise noted.

|

Looking for learning materials? Find entertaining and educational books for learning a language at Scriveremo Publishing. Just click the link below to find learning books for more than 30 languages!

| |

comments powered by Disqus