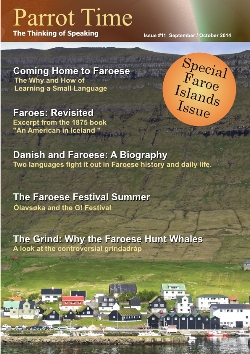

Danish and Faroese: A Biography

|

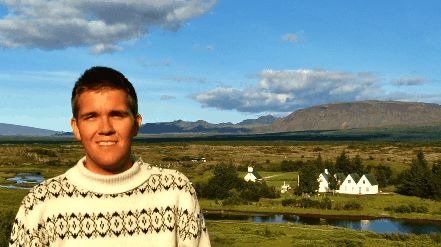

"Can you please hand me the spake?" That's more or less how it would have sounded when I asked a Danish boy that question. I was around six years old, playing out on the street on a summer trip in Denmark. I had spoken in Danish, of course — or at least in what I thought was Danish. But as his face twisted in confusion, I realized that he didn't understand the word "spake," which I had apparently invented by saying the Faroese word for spade with Danish pronunciation.  The Løgting building, parliament of the Faroe Islands, in the 1950s. The Home Rule Act was signed into law here in 1948, making Faroese the primary language of the islands. For the first time, I became aware of a definite distinction between Faroese and Danish. I remember how shocked I was at the inconsistency this incident revealed. Up until that point, I did not know exactly where the borders lay between the two languages. From what I can recall from the early years of my life, I did change the way I spoke when I was speaking "Danish," but I would just transform my Faroese words into Danish-sounding equivalents. I had picked up many of the sounds and patterns from watching children's shows in Danish, so I would try to imitate those television voices. I'm sure I had a thick accent and made other mistakes, but the Danes always seemed to understand what I was trying to say. Growing up in the Faroe Islands, one is exposed to a lot of Danish. There are a handful of Faroese-made or, more commonly, Faroese-dubbed children's shows, but they are only broadcast on the national television channel, KVF, for about half an hour a day. But children's programming in Danish can be seen practically 24/7 on satellite TV! Many other shows and movies come in English, with Danish subtitles. And it's not only television that comes to us in Danish. More books are published in Faroese per speaker than almost any other language, but our libraries and bookstores are still full of Danish titles. The operating system on our computers, the apps on our smartphones, the instructions on our washing machines... everything is in Danish, right down to the small stickers on the cheese and chicken at the grocery store. I completely understand why this happens, and that it would only make it more expensive for me, the consumer, to have everything relabelled and rewritten in Faroese. But still, it is a nice thought — to see the name of everything spelled out in my mother tongue. Danish is not only in our everyday lives, but also in our school system. We start learning Danish in the third grade, and most of us already understand and speak a little before those classes start. Until 9th grade, we have regular Danish classes, but most of the other school material is in Faroese.  The author, Uni Johannsen, in Þingvellir, Iceland, 2012. In upper secondary school, the situation is reversed. A lot of work has gone into creating Faroese material for primary school children so that they can start out learning in their mother tongue. But once we reach upper secondary school, pretty much everything is in Danish, except for Faroese class, of course. Some teachers were Faroese, others were Danish, but although most of them understood Faroese, the coursework was only available in Danish. Therefore I would study biology, chemistry, physics, history, religion, mathematics, geography, English — and, of course, Danish — all in Danish. All of this exposure to Danish meant that we were exempted from a whole year of Danish class the first year of upper secondary school, and still ended up with the exact same Danish degree as our counterparts studying in Denmark. Although we were spared a year of Danish classes, I think what we gave up was even greater. I remember how frustrating it was to do readings in Danish, knowing that I would be presenting in Faroese! Sometimes I would even sit down and translate the entire text into Faroese, so that I would understand it thoroughly. It is hard to always read technical words in a foreign language, and then to have to express them in Faroese. Many students use more international Faroese words, which are imported and therefore closer to their Danish equivalents, but I like to use our own native words, which complicates matters. The Home Rule Act of 1948 made Faroese the main language of the Faroe Islands, although Danish was also to be learnt well by all. Because of this, we should all have the legal right to write our exams in Faroese or Danish, according to our preference. But sometimes matters are not as black and white as the letters of the law. When I wrote my exams in chemistry and mathematics, I was told that it was safer for me to write my answers in Danish, since they would be graded in Denmark and there was no guarantee that the graders would understand Faroese well enough to determine if I had answered correctly. There were also cases in the 1970's in which students refused to speak Danish at their oral exams in civics, which the school required of them since the examiner did not understand Faroese. Because of this, the students did not officially graduate, but were later allowed to continue into higher education because of their special circumstances. They wrote in Danish, but spoke Faroese in their homes and fields and other interactions with their countrymen. However, we have not always had the legal write to use Faroese. Danish was for many years the language of the administration — legislative, ecclesiastic, judicial and commercial — and of the entire educational system. The language of the Church became Danish after the Reformation in 1537, in spite of the core Protestant belief that the word of God should be told to people in their native language. The Faroe Islanders, however, were told that God did not understand Faroese. Despite all of this, the Faroese maintained their own language in their everyday lives. They wrote in Danish, but spoke Faroese in their homes and fields and other interactions with their countrymen. Of course, the language was profoundly affected by years of formal disuse and heavy contact with Danish. But at the beginning of the 20th century, some schools began to offer Faroese classes, and Faroese gained equal rights with Danish in schools and churches in 1939. Finally, the Home Rule Act assured Faroese its official and dominant status within the islands. With the help of the nationalist movement, which started at the end of the 19th century, and the Faroese Language Committee, established in 1985, the Danish influence has been gradually lessened in favour of a more Faroese style and vocabulary. After all of this language conflict, we still learn Danish in school. Faroese is now the first priority, Danish is the second, and English follows closely behind as the third. Many students even study an additional language, such as German, Spanish, or French.  Road sign in the Faroe Islands, written in Faroese. I sometimes wish that Faroese had an even higher priority in our schools. If we cannot speak and write our own mother tongue flawlessly, how can we expect to master any other languages? A survey from 2004 shows that Faroese secondary school students have serious difficulties with normative Faroese grammar and spelling, so it might be best to focus a bit more on Faroese. But because the Faroe Islands is such a small nation, we really do need to be able to speak other languages — and that naturally leaves less time and energy for our own. And studies have indicated that if we were to isolate ourselves, only speaking Faroese, the language would likely be in a worse state than it is in now. We need to be able to speak some other languages if we want to have opportunities in life and a diversity of experiences. It would be quite boring to spend all of our days in the Faroes and talk only to the same 50,000 souls our entire lives, wouldn't it? For my own sake, I am very happy to be able to speak Danish. It has brought me the joys and opportunities of easy communication with all of our Scandinavian neighbours. I imagine it as a kind of bond, bringing the Faroes closer to our relatives in Norway and Sweden as well as Denmark. The Icelanders have abandoned learning any mainland Scandinavian language well, and they are drifting farther and farther from the others as a result... something I hope will never happen here. If the talk of secession ever becomes reality, I won't mind if we learn Norwegian or Swedish, or even a pan-Scandinavian mixture of all three, instead of Danish — as long as the old ties to the rest of our region are preserved. A deep connection to our linguistic and cultural past will give us strong roots as we move towards a Faroese future. |

| Danish and Faroese: A Biography | ||||||

| Writer: | Uni Johannesen | |||||

| Uni Johannesen is a 22-year-old Faroe Islander from the village of Norðragøta who is interested in science and languages. | ||||||

| Images: | ||||||

| ||||||

| Edited by Miranda Metheny | ||||||

Miranda Metheny retains all copyright control over her images. They are used in Parrot Time with her expressed permission.

All images are Copyright - CC BY-SA (Creative Commons Share Alike) by their respective owners, except for Petey, which is Public Domain (PD) or unless otherwise noted.

|

Looking for learning materials? Find entertaining and educational books for learning a language at Scriveremo Publishing. Just click the link below to find learning books for more than 30 languages!

| |

comments powered by Disqus